A Closer Look at On the Edge

By Dale Nelson

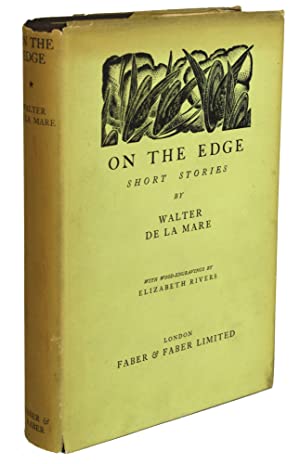

“The Line of Terror,” Arthur Machen’s New Statesman review of On the Edge (Faber & Faber, 1930) is an odd thing. He discusses only one of its eight stories, and mentions only one of the others. Still, he tells us that he liked this book of “curious and beautiful short stories.”

In contrast to Machen’s review, the present survey will talk about the plots of the other seven stories. It’s what Walter de la Mare does with his plots that accounts for most of their interest.

“The Recluse” – This is the story Machen discusses. Mr. Dash is well-named because the story ends with him—wearing a dead man’s borrowed dressing gown and slippers—making a comic early morning dash for it, once he has retrieved his stolen car key from Mr. Bloom’s bedside table. The story is eerie and, I think, maybe a bit comic too.

“Willows” – The title refers to the house in the country where the minor poet James Cotton had lived. Ronnie Forbes seeks to visit there on behalf of an American university friend. For an American, having “chanced on” a literary figure about whom only one critical article had been written was a stroke of luck and a precious opportunity to advance his career with an article of his own. The poet is believed to have died in Trinidad. Ronnie’s mission was to try to find out whatever he could from the late poet’s mother and send the details.

Mrs. Cotton talks to Ronnie, avowing her ignorance of poetry but eventually disclosing that she paid for the printing of her son’s two books. The first “slender volume” was published when he was hardly more than a teenager; and the critics were “kind.” Perhaps eight copies were sold. The second book was… not understood.

After conversation and a meal at Willows, Ronnie walks back to the village. He passes a wood, perhaps of willows (which were associated in medieval times with poetic eloquence). The “neatly clad figure of a tubby little man” hastens out of the wood and hands him an almost illegible, unintelligible poem – his most recent; an unpublished holograph, signed with the initials J. C.

But Ronnie does the right thing! He telegraphs his friend from the village: he has visited Willows but “Nothing doing. All gone. Am emphatically convinced only course to keep exclusively to text.” And he mails the new poem to Mrs. Cotton. She will understand him.

C. S. Lewis would have relished the story’s implied rejection of inquisitive academic “research.” Let the published works stand for what they are, for better or worse.

A few references to Blake suggest the idea of the poet who is regarded as insane. The story’s implication is that James Cotton really is not in his right mind; and that that is none of the public’s business.

“Crewe” – This story and “Seaton’s Aunt” (in the collection The Riddle and Other Stories) are, I suppose, de la Mare’s best-known stories of the supernatural.

Many stories from the late 19th and early 20th centuries begin with a narrator who happens to get to talking with a chance-met person in a club, on a train, or, here, at a railway station. The main story is then this person’s narrative. Here the principal story is told by a an uneducated man, a retired servant, most recently employed by an elderly rural clergyman. He observed the gardener surreptitiously stealing drinks from the pantry and, rather than do it himself, persuaded the young lad who worked around the property to warn him. The gardener ended up being fired, and hanged himself after threatening to get even with young George. After this, the narrator noticed – oddly, in a harvested field — a scarecrow where there’d never been one before, and which seemed to have been moved from time to time, appearing closer to the house. There came a night when the narrator heard questionable sounds somewhere, and he directed George to go outside and investigate while he looked around inside, although he stood quietly in the dark and listened. George’s body was found in the morning. The episode has left the retired servant with a nagging worry about the possibility of spirits returning and making use of something material by which to manifest themselves (as in M. R. James’s “‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’”). Arthur Machen got the creeps from “Crewe.”

Many stories from the late 19th and early 20th centuries begin with a narrator who happens to get to talking with a chance-met person in a club, on a train, or, here, at a railway station. The main story is then this person’s narrative. Here the principal story is told by a an uneducated man, a retired servant, most recently employed by an elderly rural clergyman. He observed the gardener surreptitiously stealing drinks from the pantry and, rather than do it himself, persuaded the young lad who worked around the property to warn him. The gardener ended up being fired, and hanged himself after threatening to get even with young George. After this, the narrator noticed – oddly, in a harvested field — a scarecrow where there’d never been one before, and which seemed to have been moved from time to time, appearing closer to the house. There came a night when the narrator heard questionable sounds somewhere, and he directed George to go outside and investigate while he looked around inside, although he stood quietly in the dark and listened. George’s body was found in the morning. The episode has left the retired servant with a nagging worry about the possibility of spirits returning and making use of something material by which to manifest themselves (as in M. R. James’s “‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’”). Arthur Machen got the creeps from “Crewe.”

“At First Sight” – Long enough to be regarded as a short novel, this story seems straightforward. Cecil Jennings has a congenital condition that keeps him from looking upwards. He knows people’s voices, but their physical presences are, for him, faceless. In his early twenties, he lives at home, dominated by his step-grandmother and patronizing Canon Bagshot among others. However, seeing a worn glove on the pavement, he feels compelled to find the woman to whom it belongs, though he doesn’t know what she looks like. She turns out to be a shopgirl, but this doesn’t matter to Cecil, whose thoughts and feelings become entirely wrapped up with her. Without his knowledge, his Grummumma arranges for Miss Simcox to have a humiliating meal at Cecil’s home, attended by members of local society. This doesn’t disillusion Cecil, however, who meets her again at their customary spot and, at last, desperately asks her to marry him. She feels she cannot consent although she admits that she loves him. She feels shame over some incidents in her past (she was seduced). She cannot bring herself to promise unequivocally not to drown herself; they part, and never meet again. But Cecil manages to raise his head and eyes for one look into her face. As to be expected from de la Mare, it’s a fine story, and it’s likely to haunt readers.

In their last talk, Cecil tells Miss Simcox, “‘I can’t think what you find in me,’” and she asks him what he could find in her. He replies, “‘I don’t find anything. I am you. You are here. Do you understand what I mean?’”

In The Figure of Beatrice (1943), Charles Williams wrote, “There is some kind of experience which can only be expressed by saying: ‘Love you? I am you’” (p. 204). Williams’s book is about Dante, but perhaps he was also recalling de la Mare here.

“The Green Room” – You might fall in love with the unsuspected book room, the “parlour annexe,” which bookseller Mr. Elliott reveals only to favored customers. After I read de la Mare’s description of it, and Alan’s choice of a volume of Herrick’s poems, and before finishing the story, well, I got up and ordered an Oxford edition of Robert Herrick. And I sighed for that book room. If I were to compile an anthology of my favorite descriptions of houses and bookstores, the green room would be among them, along with passages such as C. S. Lewis on the big old house he grew up in:

“I am a product of long corridors, empty sunlit rooms, upstairs indoor silences, attics explored in solitude, distant noises of gurgling cisterns and pipes, and the noise of wind under the tiles. Also, of endless books. My father bought all the books he read and never got rid of any of them. There were books in the study, books in the drawing room, books in the cloakroom, books (two deep) in the great bookcase on the landing, books in a bedroom, books piled as high as my shoulder in the cistern attic, books of all kinds reflecting every transient stage of my parents’ interest, books readable and unreadable, books suitable for a child and books most emphatically not. Nothing was forbidden me. In the seemingly endless rainy afternoons I took volume after volume from the shelves. I had always the same certainty of finding a book that was new to me as a man who walks into a field has of finding a new blade of grass.” (Surprised by Joy)

But this is by the way. “The Green Room” is a ghost story. The ghost may have been a disciple of Emily Brontë, who was a poet as well as novelist; the verses Alan reads in a manuscript notebook already reminded me of Emily’s before the part of the story in which Alan arranges for the poems’ publication, and an acquaintance of his, glancing at the book, alludes to the Brontës.

Here is a bitter ghost.

“The Orgy: An Idyll” – Since perhaps the 1960s or 1970s “orgy” has come to mean a number of people wallowing in gross sexual transgression, but formerly it meant (more broadly) a “licentious revel,” and so it could be used ironically but without a nasty violation of taste to refer, I suppose, to (e.g) a children’s birthday party at which a superabundance of sweets were consumed. Here de la Mare tells a story that, I suppose, Saki could have told, and would have told in about a quarter of the space; not that de la Mare’s version is padded. Philip Pim, a dependent young man who resents his wealthy but stingy guardian’s efforts to make him fit for work, goes to a fashionable emporium and, walking through one after another of its lavish departments, avenges himself by running up many thousands of pounds of charges for luxury goods to be delivered to the Colonel’s Grosvenor Square residence in town. For himself he buys an umbrella with his own money, and slips out of the store by the back way.

“The Picnic” – This ironic but sympathetic story of a capable, middle-aged London spinster’s one-sided seaside experience of romantic feeling has a twist I didn’t see coming.

“An Ideal Craftsman” – The final story is an excellent tale of the macabre centered on an imaginative young boy who discovers a murderess and, on his own initiative, assists her to throw off suspicion. His reading has prepared him for such a moment, and insulates him from the reality of that night for some minutes. De la Mare credits Forrest Reid with helping him in the writing of “An Ideal Craftsman” and dedicated On the Edge to him. Reid wrote a critical book on de la Mare. He was a friend of C. S. Lewis’s old friend Arthur Greeves.

On the Edge is almost a century old. It was written by a poet and author of prose fiction who was not afraid of adverbs. If you try reading de la Mare and his style puts you off, probably you are too much habituated to current writing.

My thanks to Douglas A. Anderson, who identified the Charles Williams quotation with dazzling celerity when my efforts to find it were stumped!

Wow – a Machen review from 1930 and this: time for disciplining the eyes to note the titles and do some more de la Mare reading, in case there are spoilers to be avoided in either article! (How I enjoyed The Return – but now Wikipedia has me wondering which version I read! : “1910; revised edition 1922; second revised edition 1945”? Ah, double-checking, I now see Wikipedia also lists the contents of On the Edge, so I need not risk the temptation to read on, yet, in order to collect the titles.)

LikeLike