The Weekly Machen

Arthur Machen was quite fond of poetry and held it to be among the greatest occupations of man. His late essay, “A Note on Poetry” (1943), is a brilliant summation of his thoughts on the matter and can be found in Dreamt in Fire. Other reviews by Machen on poets and poetry are available for reading, including Keats, Masefield and a kind word for amateurs. Here, Machen studies the nature verse of Francis Ledwidge (1887-1917), a name probably unfamiliar to most. Tragically, his life was cut short by the Great War, a fate shared by other great writers including Saki and William Hope Hodgson. Ledwidge was patronized by Lord Dunsany who also wrote the introduction to the book that Machen reviews in the following article. It is interesting to compare two great masters speaking on the same volume.

A New War Poet:

Lord Dunsany’s Discovery

by

Arthur Machen

October 9, 1915

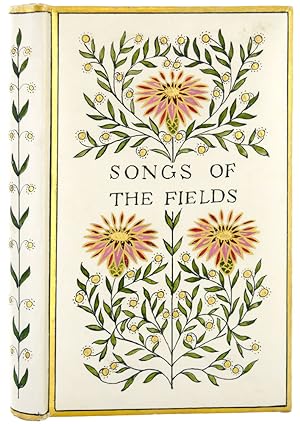

Songs of the Fields. By Francis Ledwidge. With an Introduction by Lord Dunsany. (Herbert Jenkins.)

There is a picturesque story about the book and its author. Francis Ledwidge was born in the Irish peasantry. He was a labourer on the land. He learned shorthand, hoping to be a journalist. He was a shop-assistant in Dublin. He was a hypnotist, and so banned in County Meath as a wizard. He had written verses and destroyed them till Lord Dunsany became his patron in the best sense of the term, and so these songs have been printed. And now patron and poet are fighting together in the ranks of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

There is a picturesque story about the book and its author. Francis Ledwidge was born in the Irish peasantry. He was a labourer on the land. He learned shorthand, hoping to be a journalist. He was a shop-assistant in Dublin. He was a hypnotist, and so banned in County Meath as a wizard. He had written verses and destroyed them till Lord Dunsany became his patron in the best sense of the term, and so these songs have been printed. And now patron and poet are fighting together in the ranks of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

This, I say, is a most interesting story, but as Lord Dunsany wisely cautions us, its interest has nothing whatever to do with Mr. Ledwidge’s poetry, as poetry. And neither aristocratic nor democratic, or rather, its high and low have no relation to the high and low of the political and social order. The psychologist may find it deeply interesting when the peasant becomes a poet; perhaps a more subtle psychologist may wonder how anybody save a peasant can become a poet: the inept “Baconian” will eject his futilities as to the impossibility of the “Stratford yokel” ever having written Shakespeare’s plays.

Judgement of Poetry

But in the high court of literature all those pleas and writs cease to run; the only question is as to the value of the accomplished work. And I think that these “Songs of the Fields” are of high value.

Before comment, I take an example that strikes me; not as the author’s best work, but as a text for what I am about to say:—

EVENING IN FEBRUARY

The windy evening drops a grey

Old eyelid down across the sun,

That last crow leaves the ploughman’s way,

And happy lambs make no more fun.

Wild parsley buds beside my feet

A doubtful thrush makes hurried tune;

The steeple in the village street

Doth seem to pierce the twilight moon.

I hear and see those changing charms,

For all—my thoughts are fixed upon

The hurry and the loud alarms

Before the fall of Babylon.

Now one sees, I think, in these lines an observation and expression both faithful and felicitous; note the entire fitness and happiness of that “grey old eyelid” to figure the dim February twilight. The landscape is all veiled and filmed over with grey, the rising moon is of the faintest silver, hardly illuminated, everything is still and dim, sinking into darkness and a deeper silence.

It is all very well done; but it is the last stanza that transmutes the lines from verse into poetry; when one sees the Irish peaceful village suddenly lit up by the red glare of those frantic torches that rushed and hurried and flamed to and fro in the awful hanging, groves and terraces of Babylon.

Picture of Eternity

It is with difficulty that I express my meaning—for poetry by its definition is the last and essential truth, which can be defined no farther; but I would say that the poem of “Evening in February” seems to me to picture eternity itself.

It is with difficulty that I express my meaning—for poetry by its definition is the last and essential truth, which can be defined no farther; but I would say that the poem of “Evening in February” seems to me to picture eternity itself.

Then there is a minor consideration. It is this; that though the author has been a peasant and is a poet; he is not what is called a peasant poet. Burns was a peasant poet; and when Carlyle remarks on the sad disadvantages of Burns’s education he told the truth in a manner that he little suspected. The true disadvantage of Burns’s education was that he had any. It was his misfortune that he smattered a little cheap learning, and so called the sun Phœbus instead of plain sun. His true education was in the tradition of the Scots poets that were before him, in the legend and fairy tales of the country that the old woman taught him when he was a child, in the Scottish breath of the winds that blew upon him. It was well that he knew few books, it bad been better if he had known none.

Quite otherwise is the case of Mr. Ledwidge. The poem that I have quoted is a “literary” poem; that is, it is the work of a man who has been influenced profoundly by his reading. Its phrasing shows that; that “grey old eyelid” could only have been written by a lover of books. And so the illuminating appearance of Babylon: that is a touch that speaks to the lettered man.

Now and again, it must be said, he does strike a certain Celtic note, but it is the simplicity, not the glamour, of the Celtic spirit that he attains. Thus:

Had I but wealth of land and bleating flocks

And barnfuls of the yellow harvest yield,

And a large house with climbing hollyhocks

And servant maidens singing in the field,

You’d love me.

is Celtic in its primitive simplicity, not only of manner, but of fact.

Previous: The Celtic Paradise

Next: