The Weekly Machen

Over the next few weeks, we will be presenting three front-page features by Arthur Machen as star reporter for the Evening News. In each, Machen serves as an eyewitness for readers to historic royal events including a coronation of a king. Interestingly, none of these features are listed in the excellent bibliography by Goldstone and Sweetser. For the first, Machen is present at the unveiling of the grand Victoria Memorial, which despite its opening in 1911, was not completed until 1924.

A Study in Scarlet:

Personal Impressions of an Historical Occasion

by

Arthur Machen

May 16, 1911

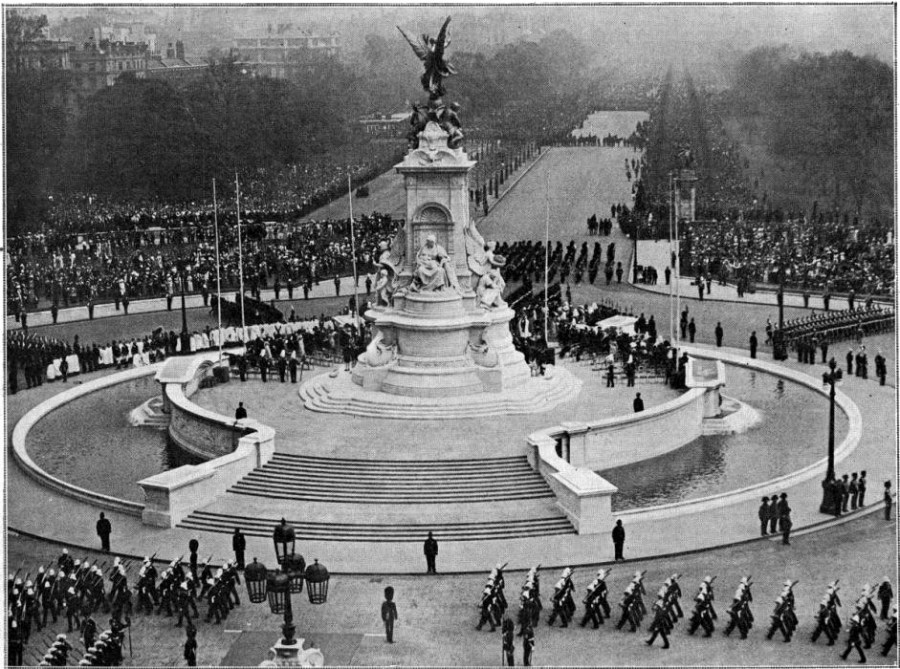

It is, I should think, doubtful whether any such spectacle as that which I witnessed to-day at the unveiling of the Queen Victoria Memorial has ever been seen in England, or perhaps in the world. So far as I can see it must be unique.

In the first place, the setting. Technically, we are still in spring; but this morning it was full summer.

The sun shone hot, through a dim haze—such a tender mist as is only to be seen in England—and there was the faintest of all breezes; you could feel now and again a cool faint breath on your cheek, and the green leaves on the tree-tops were just stirring.

And these leaves were full green at last, after long winter and the dark mourning of the year; and the grass was still fresh from showers; the trilling and singing of birds came from the grove island on the lake: summer was truly come in.

Massed Crowds

My place was on the walk, and on all sides Buckingham Palace and the Memorial were compassed about by thousands. They streamed towards their centre from all quarters and by every avenue of the Park; they were massed, thick and impenetrable, by eleven o’clock.

And, looking towards the white and gold group of statuary, and at the seats arranged before it, the difficulty was to take in the quite extraordinary variety of the costumes worn.

At a Levee you may, doubtless, see more gentlemen in the correct black velvet coat and breeches, silk stockings, and cocked hat; at a Review there are more military uniforms; at a University convocation more of the doctors’ scarlet; in the Guildhall a greater display of purple robes edged with fur; and at a Delhi Durbar, a far finer show of gorgeous oriental vestments.

But to-day in the sunlight, all these strange varieties of costume and attire met together: Highlanders talked to major-generals and a prince of Siam might chat with an Admiral of the Fleet.

The Roll of the Drums

And all the while from one quarter or another came the beating of the drum, the loud word of command, and the clamour and summons of the bugle, that has so often called men to violent battle and the shock of death. That even in the greeny park on the day of festivity, its clangorous, insistent voice was not without the note of terror.

The scarlet soldiers marched and countermarched about the ground, their bands played exultant music, their bright bayonets glittered in the sun as they made their measured way between the massed civilians.

Before the veil, still in its place, was a group of brilliant uniforms; I could see from far that some of them were of the armies of India.

The costumes of the nobles of India caused some odd reflections.

‘‘Did you see that lady who went by just now?” said a policeman to me. “He turns out to be a gentleman.”

The prince in question was like the King’s daughter in the Psalm; his raiment was, literally, of wrought gold, and in the summer light it shone and glittered gloriously.

Mere coincidence had been at work in colour. At first, looking at the great semi-circle of privileged guests, one would have called it a kaleidoscopic pattern of all hues and tinctures; but gazing more attentively, scarlet uniforms, parasols, and costumes in the key of blue—ranging from the most fairy lilac to the darkest purple—and white plumes and white dresses made up the imperial colours of red, white, and blue.

The Palace of Gloom

Strangely enough, and unfitly enough, the only touch of gloom in this wonderful and brilliant and ever-changing picture was the sad and almost squalid facade of the Palace. The bright marbles of the memorial made its stuccoes look sadder than ever; but even the Palace had its redeeming touch of brightness; its housetops were alive with sightseers, and amongst them here and there was the scarlet of the royal uniform.

The time was drawing near. On the pedestal of the memorial, amidst the brilliant uniforms of the whole world, shone the brightness of the Cross as the Archbishop took his place.

Then the throbbing of a drum grew to a louder beat, a drum-major headed his band, tossing his great baton into the air as he marched, sailors in blue wearing straw hats followed, and took up their places under the archway of the Palace.

From the other side of the courtyard a mass of scarlet, glittering with bayonet blades, advanced and faced them; again and yet again there rang out the strident word of command. Facing the veil a mass of military colours, all gorgeous in crimson and gold, had been grouped together.

The air grew cooler as the clock went on to twelve; a dark cloud had gathered in mid-heaven, and a brisker breeze sprang up. People were grateful for the refreshment of the shade and the wind— if only the cloud would not break in thunder.

The Yeoman of the Guard

Then, as noon began to ring, the command sounded anew, and the Yeomen of the Guard marched with slow, dignified steps out of the Palace; after them the great officers of State, and all the majesty of England and Germany, walking in long precession: the King of England and the Emperor of Germany first. And the sun shone out again.

The long array climbed the blue carpeted steps of the pedestal, and the trumpets sounded.

Without the boundaries the crowd pressed and swayed and murmured, endeavouring to see the splendid spectacle. Scarlet now was the one colour beneath the memorial; scarlet and heavy gold, following the example of King and Kaiser, who both wore the uniform of a Field-Marshal of the British Army.

At first no voices and no sound of words reached the onlookers by the lake; it was as if some great and solemn and significant ritual was being performed in dumb show behind the scarlet hedge of the Yeomen. But the golden cross was lifted up, and we knew that the Archbishop of Canterbury was dedicating the memorial to the glorious memory of Queen Victoria.

To the Glory of God, and in memory of our Gracious Sovereign Lady Queen Victoria, we dedicate this Memorial in the Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Amen.

And the master of the music raised his baton, and the bands and massed choirs begin to sing and play the old hymn “O God our help in ages past.” But though six choirs were singing, very faintly their voices came to us in the open space by the water.

Then a great summons of command, arms rose to the present, the crimson and gold colours were lifted up; and the veil sank away and vanished.

The bands thundered out the National Anthem, there was a thundering cheer as the marble figure of the Queen shone out; and then the louder thunder and reverberation of the cannon as the salute of great guns was shot off.

The rite had been performed, and there in marble stands the great memory of a great reign.

A great march-past of sailors and marines and soldiers followed. Detachments, as it seemed, from every regiment in the service wheeled past the Memorial with bands playing and colours flying.

The bright swords gleamed at the salute as the steps of the great monument were passed: Te mortuam sed in æternum vivam salutamus—we salute the dead, but living for evermore in memory—that seemed to be the symbol of the blazing scarlet and the flashing steel.

Then the procession was reformed; the National Anthem rang out once more, and to a tumult of cheers, the royal party returned to the Palace.

Previous: Some Autumn Books

Next: The Enchanted City

Very vivid – thank you! Only 37 days until the Coronation of George V and Queen Mary (already King and Queen for a year) – and only 17 months till the First Balkan War. “King and Kaiser, who both wore the uniform of a Field-Marshal of the British Army” – only 30 months until Saki’s When William Came: A Story of London Under the Hohenzollerns was published (how cheeky – and/or how probable did it seem, by then?).

As to “arms rose to the present, the crimson and gold colours were lifted up; and the veil sank away and vanished”, this was filmed by Pathé – and ” reissued as part of Pathe’s 21st Anniversary […] shown too fast but at the correct speed for the soundtrack” (!), and happily available on YouTube entitled “The Unveiling Of The Queen Victoria Memorial (1931)”.

LikeLike