The Weekly Machen

The following book review begins with a brief, but insightful reflection on memory and recollection. At one point, Machen mentions an culinary event which he experienced at the age of ten with its unfortunate taste still in his mouth. Quite obscure today, Ralph Neville (1865-1930) seems to have been a writer with a wide array of interests as a short list will attest: Notes on the Restoration of Goldaming Church (1880), British Military Prints (1909), London Clubs: Their History and Treasure (1910), and Sporting Days and Sporting Ways (1910). Nevill’s reminiscences in the following excerpts show him to have been an honest writer who did not overlook the foibles of the past.

The following article is not listed in the bibliography by Goldstone & Sweetser.

Looking Backward:

“Fancies, Fashions and Fads” of Old Days

by

Arthur Machen

December 30, 1913

There is a kind of alchemy in the art of recollection. Most of us, I suppose, have fallen now and again on very rough places in the journey of our mortal pilgrimage. I can look back on my past life and think of lots of occasions on which I was profoundly ill at ease; I remember small discomforts and great miseries, bad dinners, unkind remarks, moments of anguish even are to be recalled easily enough. I shall never forget a horrible boiled scrag of mutton and a rice puddle—I will not call it a pudding—of which I was made to partake in the city of Hereford in the year 1873. It was in the same city that the roast fowls were undone and showed pink joints. This was in 1877, but the nasty letter from an editor was dated 1890.

There is a kind of alchemy in the art of recollection. Most of us, I suppose, have fallen now and again on very rough places in the journey of our mortal pilgrimage. I can look back on my past life and think of lots of occasions on which I was profoundly ill at ease; I remember small discomforts and great miseries, bad dinners, unkind remarks, moments of anguish even are to be recalled easily enough. I shall never forget a horrible boiled scrag of mutton and a rice puddle—I will not call it a pudding—of which I was made to partake in the city of Hereford in the year 1873. It was in the same city that the roast fowls were undone and showed pink joints. This was in 1877, but the nasty letter from an editor was dated 1890.

These events were saddening and exasperating enough at the time of their occurrence; yet recollection alchemises them. Meminisse juvat; it is pleasant to look back even on the most unpleasant incidents; to realise that ill-favoured scrags of mutton, disappointments, rebuffs, and sorrows have been encountered and in some sort or another overcome. I don’t quite know why this is so, I don’t quite know why the commonest objects acquire interest and value if they are old enough; but so it is. The other day passing by a curiosity shop, I saw a small porcelain jar exhibited in the window. On the cover was a picture of a salmon with a background of greenery. I remember eating potted salmon out of just such a jar as this, and when the salmon was all eaten, the pot that held it was thrown on the rubbish heap. Now it has become a curiosity, a thing to be collected.

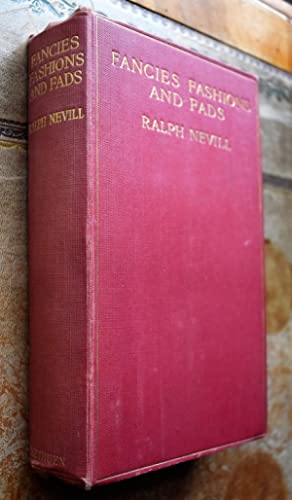

It is by the operation of this obscure “law of the old” that Mr. Ralph Nevill’s “Fancies, Fashions and Fads” (Methuen) makes such extremely pleasant reading. The author is not without his comments—acute enough for the most part—on things and men and notions that are still with us; but a great portion of his book has the character of reminiscence. “This or that or the other,” he seems to say, “once was and is now no more,” and whatever this or that may have been, a grave matter or a gay matter or a mere trifle, one likes to hear about it because it is past and over. Even the jar that held the potted salmon of 1870 is interesting in 1913; and if it last uncracked till 1953 it will have become a most valuable object.

So there is a pleasure in reading Mr. Nevill’s recollections of the Savoy Hotel in its young days.

The original Savoy restaurant was certainly one of the most agreeable dining places the world has ever seen, for in addition to the excellent food the eye was gratified by hosts of pretty women. Compared to the present palatial dining halls, it was, of course, quite a small place, but those who remember the halcyon days of 1895 will agree that nothing so bright and pleasant has been seen since. Few, alas, of the habitual frequenters who waited in the little passage (on the walls of which hung framed the first sovereign ever taken at the Savoy) while (after the manner of her kind) a fair companion lingered in the cloakroom are still enlivening the West End; the fall in stocks and shares which followed the South African war sent many of them to far less amusing places.

The revel itself may, perhaps, have been a little crude in its colour scheme; but the flaring hues have faded in the crucible of recollection; scarlet has become almost rose tendre.

But here is something both old and new. It is the story of a practical joke that was engineered in the fading ‘nineties, and for once in a way there was a practical joke by which no one suffered; though Sir Augustus Harris’s sense of dignity may have been a little touched. A gentleman, who is now a member of Parliament, smuggled a lifelike dummy of Sir Augustus Harris into his box at the Covent Garden Ball.

This dummy, worked from behind, was made to perform such antics that a crowd soon assembled below, astounded and scandalised to see such behaviour on the part of the well-known manager, who at intervals appeared to be toasting those below. All of a sudden an altercation seemed to arise, and Sir Augustus was seen to be engaged in a bout of fisticuffs, which, amidst cries of “Shame!” terminated in his falling over a chair at the back of the box.

There are some weighty remarks on the decadence of the English nobility: their loss of prestige and of power during the last thirty years. Mr. Nevill thinks that the morals of society are much the same as they have always been; it is the sense of dignity, of old tradition that have been lost.

The days have indeed gone when any attempt at arrogance on the part of men or women of Semitic extraction was sternly and promptly suppressed.

“I am sorry I cannot send Mr. X— an invitation to my party,” wrote a wealthy heiress of Hebrew parentage to one of her husband’s relatives who had asked for a card for a friend, “as you must realise he is not of mon monde.”

“I agree with you about Mr. X— not being of your monde,” came the reply; “his father was not a Jew banker, but only an English gentleman of ancient family.”

The old English gentleman Mr. Nevill pictures as stiff, cold, rather narrow, full of racial pride, and holding aloof from the rest of the world, “whom at heart he tolerated only on sufferance.” But at the same time he was a man of the strictest honour and of indubitable courage; always just and kindly to those beneath him in the social order. His main fault was “a lack of that flexibility of mind which is unfortunately too superabundant in the modern patrician.” Sir Leicester Dedlock is a perfect portrait of the type.

There is a note of pessimism amidst the gaiety of the book, and the writer does not seem an enthusiast in the cause of democratic government. He notes, indeed, that democracy produces and has always produced a greater number of swindlers and charlatans than the worst forms of autocracy. This is a phenomenon that others have observed.

Previous: How We Lost Our Tails

Next: The Rare Gift of Literary Individuality