The Weekly Machen

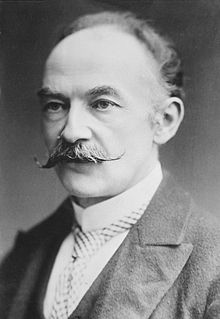

Arthur Machen, the former actor turned roving reporter, filed this dispatch after observing a rural rehearsal of Thomas Hardy’s “The Three Wayfarers.” He accomplished much of what is expected of such an assignment: a vivid description of the Dorset countryside, a brief history of the play, a dose of pre-production details and an interesting summary of the narrative. Yet, his eye caught something brilliant that may have gone unnoticed by another journalist. The result is an ending which is elegiac and haunting.

Thomas Hardy as Playwright:

To-morrow Night’s Performance

by

Arthur Machen

November 14, 1911

The railway line leaving Bournemouth, its trim villas and such pines have been left to it, soon penetrates into a wilder and more lovely land.

The railway line leaving Bournemouth, its trim villas and such pines have been left to it, soon penetrates into a wilder and more lovely land.

After passing the calm waters of Poole Harbour, shining in the afternoon sunlight, I began to think of Hardy, and of that mystery of visible nature which I have always thought to be the prime secret of the great master’s work.

We sped though a wide level, a place of rough lands and rough gorse and brown thickets of bracken. Here and there was the gleaming of water, and far away the vague outline of the downs, a remote, undiscovered country.

In the midst of this plain Dorchester surges up. The chief street begins in the low land and climbs up a long hill, and vanishes into an avenue of bare, gnarled trees, whose boughs meet and intertwine. From the height of this avenue I looked down on the town. The sun had set, and the sky had hazed into dim violet, flecked with fading roses, and the smoke of the town rose slow and straight into the still twilight air. And, turning away from Dorchester, I looked through the black, twisted boughs of the bare avenue, away to the far, mysterious downs; and I could well imagine one of Mr. Hardy’s “Three Wayfarers” making his swift and shuddering flight from the gibbet and the hangman’s rope that awaited him, casting one look at the twinkling lights of the town behind him, and seeking the refuge of those distant, glimmering hills.

A Scene at Rehearsal

To-morrow night “The Three Wayfarers” is to be played at the Dorchester Corn Exchange by the local dramatic and debating society. The version has been made by Mr. Hardy himself from his story. “The Three Strangers” in the “Wessex Tales”; and if I remember well, the tale was called “Strangers at the Knap” when it first appeared in magazine form. The three are a condemned man, his brother, and the hangman; and chance brings them all together in the lonely shepherd’s cottage, at the top of the bare hill.

I found brisk preparations going on at the Corn Exchange in the grave old Georgian street. Mr. Tilley, the stage manager, was in the middle of a scene rehearsal, not for “The Three Wayfarers,” but for the other play that is to be produced, “The Distracted Preacher,” and adaption by Mr. A. H. Evans from Mr. Hardy’s tale of old smuggling days. Mr. Tilley pointed out to me the difficulties to be surmounted: the stage is somewhat shallow, and the cloths cannot be “flied.”

I returned to the Corn Exchange in the evening and found that the open-air scenery of the smuggling story had given place to the interior of the shepherd’s cottage, where the three wayfarers meet.

The “property man” of the Dorchester Dramatic Society was fixing candles into old brass candlesticks; there were duly placed on the high mantelpiece L—to the spectator’s right—while on the other side of the stage there stood a sturdy cask of mead—a drink which the Dorchester people tell me is still made in the Dorset countryside. And a very old man, who might almost have been survivor from the Mellstock Quire in “Under the Greenwood Tree” was striking his tuning-fork against the barrel and screwing up his fiddle strings to the proper pitch.

I asked one of the players about the old fellow, and I was told that my conjecture was right, or almost right, “That old man is one of the last of the old fiddlers who used to go about from one village to another, playing at fairs and merrymakings.”

Mr. Hardy’s Personal Interest

All the players are full of gratitude to Mr. Hardy. He has not only given their dramatic author permission to adopt his novels for the rustic stage, and furnished them with his own version of the “Wayfarers,” but he has been so kind as to take a great interest in the rehearsals and to furnish the actors with some most valuable hints as to the country dances and also as to points of dramatic presentation of the characters.

But as we were talking the band began to play, and the curtain went up on the revelry at the shepherd’s christening party. Round and round the merrymakers danced and galloped to a lively old tune, and there was the old man, the last of the country fiddlers, playing his bow with all his good old heart. They had put a smock over his black coat, and I thought it was strange that the old boy now wore as costume the habit which no doubt has been his customary dress in Dorset lanes and fields and on cheerful village greens for many a long year.

The rehearsal went capitally. Just as the shepherd suggested that after their dancing the neighbours might like to wet their whistles the first stranger—the man who had fled from prison and the rope— entered.

Another dance, and the second stranger, the hangman, appears. He talks grimly of his business without naming it—he has work to do early the next morning—work that must be done. Then he speaks of this odd trade of his; it sets a mark, he says, not only upon himself, but upon his customers.

The Escape of the Sheep-stealer

He is sitting in the chimney corner by the condemned sheep-stealer who had broken prison; and at last the hangman, asked about his trade, breaks into a terrible song of the gibbet and the rope. And the shuddering man next to him joins in the chorus.

And in the midst of it the third wayfarer enters and recognises his own brother, whom he imagines to be in gaol under sentence of death, sitting next to his destined executioner. He rushes out in horror; the gun booms in the distance, signifying that a prisoner has escaped, and everybody (save one alone) concludes that the runaway is the man who has fled from justice.

They all rush out in pursuit; presently the escaped prisoner and the hangman return, and again the executioner fingers his horrid hemp, and praises the merciful tightness of the knots he knows how to draw.

So the little play moves to its happy ending, to the safe escape of the poor sheep-stealer.

There is a last dance: it was brave to see the old fiddler wagging his head in time with bow and elbow. I am told that this dance is “the College Hornpipe,” used here by Mr. Hardy’s special direction and advice.

There is a last dance: it was brave to see the old fiddler wagging his head in time with bow and elbow. I am told that this dance is “the College Hornpipe,” used here by Mr. Hardy’s special direction and advice.

And so the play ends with rejoicing, and the curtain falls on this happy and enchanted glimpse of the old English life. There were horrible things in this life; even in the last dance that hangman in his shiny black suit capers hideously, and uses his rope in give effect to his fandangoes. Still, if the terrors have gone, so, I am afraid, the ancient mirth has departed for ever.

The old man whom they dressed up in the smock cannot live for many years; and there is no one born to whom he can leave his fiddle.

Previous: The Death of Thomas Hardy’s Old Fiddler

Next: The Joy of Eating

Many thanks! This so vivid – how I would like to see – and hear – it, now! At least we can easily read it, in a 1944 facsimile reprint of a 1893 American edition, bracketed with lots of interesting editorial material, scanned in the Internet Archive. Its Chronological Check List includes, under the 1911 Dorchester performance, “Shepherd Fennel’s Dance”. On YouTube I can only find orchestral and piano versions by Henry Balfour Gardiner (1877 – 1950), one with the note “It dates from 1911 and was inspired by an episode in Thomas Hardy’s Wessex Tales.” Happily, there are lots of versions of the (famous – my ear recognizes) College Hornpipe, including ones for fiddle, one of which, on the hannaford music education channel received another fiddler’s comment “thank you for playing at a pace that one could actually dance to”. I note of more general interest the Seven Dials Band – Topic (automatically generated by YouTube, with the whole of their album, The Music of Dickens and His Time) – which includes a (to my mind more Melstock Quire) version.

LikeLike

Hmm… I see that the mighty folks at YouTube have also generated The Mellstock Band – Topic with three complete albums of Hardy-related music!

LikeLike