Richard Chenevix Trench’s The Study of Words

By Dale Nelson

In 2024, something by Arthur Machen demonstrating that he was acquainted with Trench’s Study of Words came under my eyes. I resolved to write a Books Around Machen column about it. Where did Machen mention the book? Now I don’t remember.

In 2024, something by Arthur Machen demonstrating that he was acquainted with Trench’s Study of Words came under my eyes. I resolved to write a Books Around Machen column about it. Where did Machen mention the book? Now I don’t remember.

In any event I would have wanted to get hold of The Study of Words: Lectures Addressed (Originally) to the Pupils at the Diocesan Training School, Winchester. It’s mentioned favorably in Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of her friend Charlotte Brontë, and Trench’s philological writing was not forgotten a century and a half later when Owen Barfield gave an interview late in his long life to G. B. Tennyson. A catalogue of C. S. Lewis’s personal library made in 1969 records a copy. Could Tolkien have been ignorant of this work of popular philology? For sure, it’s an Inklingsy book.

First published in 1851, Trench’s Study went through a number of editions. It still deserves attention.

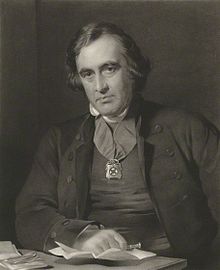

Trench (1807-1886) was an English clergyman who eventually became the Anglican Archbishop of Dublin. Back then, someone could be a high-ranking Anglican clergyman and a robust adherent of orthodox theology at the same time. Trench’s Christian faith, his erudition, and his love of his subject and its potential for entertainment are combined in this little volume.

Trench is a Christian philologist. “God gave man language, just as He gave him reason,” and language is “his reason coming forth, so that it may behold itself.” And man “could not be man, that is, a social being,” without them both (4th edition, 1853, pp. 14-15). Just how did God do this? “How… this spontaneous generation of language came to pass, is a mystery, even as every act of creation is of necessity such” (p. 16).

In other words, man is a mystery; Trench recognized this and, in his way, Machen also did. Apprehension of the mystery of man naturally leads Trench to talk about moral realities signified by words.

To start with the verbal cesspool, it must be recognized that the moral dimension of language includes the words that (in Trench’s day) were “not allowed to find their way into books, yet which live as a sinful oral tradition on the lips of men, to set forth that which is unholy and impure” (p. 30). (Today some of those words appear even in the titles of widely available books.)

There’s more to Trench’s discussion of the moral dimension of words than censure of outright foul language. He finds it “a melancholy thing to observe how much richer is every vocabulary in words that set forth sins, than in those that set forth graces” (p. 29). This disproportion is a consequence and sign of man’s fallen state. “God hath made man upright; but they have sought out many inventions” (Ecclesiastes 7:29); so words are devised because we have to be able to think, in words, about that fact and discuss it. Trench finds that words formerly possessed of innocent meanings are often “dragged down” to refer to the sinful or shameful. “Thus ‘knave’ meant once no more than lad,” and a “boor” was a farmer, a “varlet” was a serving-man, a “churl” a strong man. “Time-server” didn’t have the connotation of cheating an employer that it developed, “crafty” and “cunning” referred to “knowledge and skill,” and “retaliation” could refer simply to “the again rendering as much as we have received” (pp. 30-32). Can you imagine saying, Can you imagine saying, “Gordon loaned me his mower, and I was happy to retaliate by letting him borrow my new electric drill?” The word is now used exclusively for striking back in some way.

Happily, occasionally words may come to have nobler meanings than they used to; for example, words such as “sacrament” and “regeneration” with their present-day theological meanings (p. 36).

Trench is an author like Coleridge, in that he knows morality is more than, say, the rote deploying of “wise saws and modern instances,” but is a signature of the human being, a distinguishing mark, as Machen liked to say art is.

Trench’s lecture on the moral dimension of language concludes with these questions:

“Must we not own… that there is a wondrous and mysterious world, of which we may hitherto have taken too little account, around us and about us? And may there not be a deeper meaning than hitherto we have attached to it, lying in that solemn declaration, ‘By thy words thou shalt be justified, and by thy words thou shalt be condemned?’” (p. 59)

His next lecture, “On the History of Words,” reminded me of Owen Barfield’s book with a similar title, History in English Words, and of C. S. Lewis’s late book Studies in Words. Trench tells us that, when we refer to food animals while they are alive, we use words of Saxon derivation, but when they are prepared for eating, we use Norman ones – sheep/mutton, calf/veal, ox/beef, deer/venison, etc. (p. 65). Trench shows that “vast harvests of historic lore [may be] garnered often in single words” (p. 67). There follow discussions of words such as “dunce,” “poltroon,” Juliet’s “mammet,” “bigot,” etc. The name for a violet gem, “amethyst,” proves to have a surprising connection with alcohol and drunkenness (p. 91).

The lecture “On the Rise of New Words” is also proto-Barfieldian in its approach to something close to the latter’s “evolution of consciousness” as witnessed by, and facilitated by, the formation of new words (from existing roots, p. 110). “’Soliloquium’ seems to us so natural, indeed so necessary a word, this ‘soliloquy,’ or talking of a man with himself alone, …that it is hard to persuade oneself that no one spoke of a soliloquy before Augustine, that the word should have been introduced, as he distinctly informs us that it was, by himself” (pp. 127-128). Selfishness is almost as old as the human race, but “selfish” is a word we owe to the self-probing English Puritans (p. 129). Trench quotes an author (whom he doesn’t name): “’Language is often called an instrument of thought, but it is also the nutriment of thought’ or rather it is the atmosphere in which thought lives’” (p. 140).

A lecture “On the Distinction of Words” deals with a matter about which we’re all liable to carelessness, namely using words without due regard for nuances of meaning. For example, Trench enlightens the reader about how “hate,” “loathe,” “abhor,” and “detest” do not mean the same thing (p. 162). I was reminded of H. P. Liddon’s eulogium on Edward Bouverie Pusey, the Tractarian leader and Hebrew scholar:

In our day many ingenious theories have been put forth as to the origin of language. But Dr. Pusey believed that the only one which does justice to what it is in itself and to its place in nature as a characteristic of man is the belief that it is an original gift of God; the counterpart of that other and greater gift of His, a self-questioning and immortal soul. Language is the life of the human soul, projected into the world of sound; it exhibits in all their strength and delicacy the processes by which the soul takes account of what passes without and within itself; in it may be studied the minute anatomy of the soul’s life – that inner world in which thought takes shape and conscience speaks, and the eternal issues are raised and developed to their final form. Therefore Dr. Pusey looked upon language with the deepest interest and reverence; he handled it as a sacred thing which could not be examined or guarded or employed too carefully; he thought no trouble too great in order to ascertain and express its exact shades of meaning…

“The Schoolmaster’s Use of Words” closes Trench’s book. He believes that such etymological pursuits as the book has exhibited right up to its last pages could be enjoyable to students and of patriotic and religious benefit to them. Some homeschooling parents might find inspiration in The Study of Words.

You’re kept on your toes, spiritually, when reading The Study of Words, or you need to be. Trench’s book provides information in a lively manner, and it should also refresh the soul.