NEW POETRY

Answering the Fool by Joshua Alan Sturgill

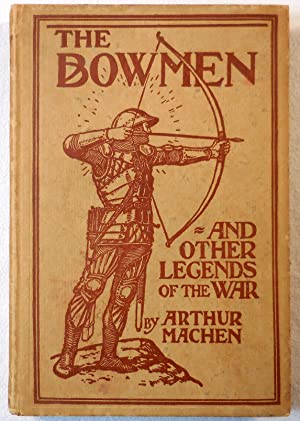

The Bowmen on the Battlefield: It was written as a tale. It was frank fiction. It did not pretend to be a narrative of anything that has occurred on the battlefield. There was no more reason for taking it to be descriptive of an actual experience than there is for regarding “The Great God Pan,” or any other of Mr. Machen’s famous stories as a string of plain facts that any lawyer would put into an affidavit.

The popularity of the Bowmen as genuine figures must be related (as Machen almost says) to the vogue for spiritualism at the time, in which bereaved parents might attend seances in hopes of communicating with their lost “boy” now on the Other Side. I think Machen was put off from such things more by distaste for quackery and fraud than by the Bible’s stern prohibitions of mediumship. In any event we must be glad that he didn’t succumb to it.

LikeLike

Re-enjoying earlier today Simon Stanhope’s Bitesized Audio Classics reading of William Thomas Stead’s 1886 story, “How the Mail Steamer Went Down in Mid-Atlantic”, I was saddened by the reminder in the introductory note that Stead “developed a strong interest in the subject of spiritualism”, writing widely about it “from he 1890s onwards” (though he does not say – and I have not tried to discover – how critically, or otherwise, an interest) – and there is of course Arthur Conan Doyle (!) – even before the terribly many Great War deaths.

LikeLike

This article says “St. George and the Bowmen of Agincourt came to the help of the English.” And that is what Machen specifies in the last sentence of his story. He has some discussion of this in the Introduction of the book-publication of this and other stories, but I have no idea how much he discusses it elsewhere – though later in the Introduction he refers to “the strong statements that I have made on the matter” with respect to “bowmen” as distinct from “angels”. The choice of Agincourt bowmen is interesting not least because presumably most of the bowmen were not killed at Agincourt, but also must in the ordinary way of things have also been dead for more than 400 years. They, at Agincourt, like the Latin-scholar soldier in their day, seem to have invoked the martyr, St. George, equally successfully in some sense. And Machen says the Latin-scholar soldier “knew that St. George had brought his Agincourt Bowmen”. Is this something like ‘time-travel’ or times somehow meeting as later in Charles Williams’s Descent into Hell or Tolkien’s unfinished Lost Road and Notion Club Papers?

Another interesting aspect is the ‘martyrological’. Trying to learn more about the “lilies” in Machen’s story in the same volume, ‘The Monstrance’, I encountered Holman Hunt’s painting, The Triumph of the Innocents via the Wikipedia article, “Massacre of the Innocents”. This painting reminded me of Elizabeth Goudge’s short story, “By the Waters of Babylon” – which I now suspect may be implicitly referring to, as it varies, the ‘matter’ of Hunt’s painting. (Just now, I find via the Wikipedia article, “William Holman Hunt” a Project Gutenberg transcription of a booklet of his which includes his date of “February 23, 1885“! – which I have not paused to read…) Is there some sort of late-Nineteenth- and Twentieth-century body of English ‘martyrological’ art and fiction?

LikeLike

Interesting threads of thoughts.

It is known that Machen had a great appreciation for The Time Machine: https://darklybrightpress.com/machen-on-martians/. Yet, my feeling is that it had little to do with science fictional purposes and I don’t believe he had instinct for that genre. However, the common assumption that “The Bowmen” should be classified as a ghost story rings hollow. Rather, St George and his bowmen are living persons in the classical Christian understanding of sainthood, who through Grace, is ever-present, and like Angels, may intercede and intervene in the affairs of “living” men. I think this coincides with AM’s worldview, but it’s all theory!

“Is there some sort of late-Nineteenth- and Twentieth-century body of English ‘martyrological’ art and fiction?” I hope so! An exciting possibility!

LikeLike

I have started trying to look around with respect to an ‘modern’ English tradition of ‘martyrological fiction’, and have not gotten very far, but did encounter a couple interesting things.

My first thought was simply ‘fiction about martyrs’ as Tennyson’s Becket sprang to mind – which I encountered and skimmed in high school when I was enjoying Anouilh’s and Eliot’s plays, but have never yet read (!). Now, I have learned that Henry Irving arranged a version for the stage in 1893, of which there is a 1904 reprint in the Internet Archive. The English Wikipedia article on Tennyson’s play also says “The actor Frank Benson became closely associated with the title role for many years, and played it in the 1924 silent film adaptation made by Stoll Pictures and directed by George Ridgwell.” An interesting Machen connection – at least as far as Benson himself goes! This led me to the Wikipedia article on the film, and both led me to the work of Rachael Low, whose The History of the British Film 1918 – 1929 (published by Allen and Unwin, who also published Tolkien!) includes a photo of Benson as Becket. Another intriguing work encountered was Rudolf Hübel’s German doctoral dissertation, with a first chapter on Irving’s version as well as Tennyson’s original, accepted in 1912, and published as Studien zu Tennysons “Becket” in 1914!

Then, I ran into a copy of George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan. Reading around in the extensive “Preface” I found him discussing, among other things, Andrew Lang’s The Story of Joan of Arc, The Maid of Orleans (1906), which I then enjoyed both in the handsome Library of Congress copy of an American edition scanned in the Internet Archive and in the LibriVox audiobook version. In it, Lang says “On the day of her burning, the Bishop and the rest went to Joan again, and wrote out a statement that she left it to the Church to say whether her Voices were good or bad. The Church has decided that they were good, and has given Joan the title of ‘Venerable,’ which is the first step toward proclaiming her to be one of the Saints. Whatever the Voices were, she said they were real, not fancied things.” Earlier he says “She not only heard Voices, but she saw shining figures of the Saints in heaven. […] These Saints were St. Margaret, St. Catherine, and the Archangel St. Michael.” Not long after its publication – on 11 April 1909 – Joan was Beatified. That is only a little over five years before the beginning of the Great War. Both St. Catharine and St. Margaret are martyrs. And, as the Feast of “Saint Michael and All Angels” in The Book of Common Prayer translates Revelation 12:7 in the Epistle Lesson, “Michael and his angels fought against the dragon”. It seems not unlikely that the recently Beatified Joan as martyred soldier with martyrs and St. Michael as Lang quotes Joan “teaching me how I was to behave and what I was to do” may be something of a pattern in the background to several of Machen’s stories.

LikeLike