The Weekly Machen

The following article, the 100th installment of The Weekly Machen series, presents us with another strange miscellany of “odd volumes” and entertaining comments from our well-read reporter. Machen’s favorite author Dickens is mentioned, as well as an obscure book Machen clearly disliked. As usual, I have attempted to link to copies of the discussed works. I’d like to thank the loyal readers of this series for their continued encouragement.

The following article is not listed in the bibliography by Goldstone and Sweetser.

Odd Volumes:

A Pecksniff Picture and a Puzzling Inscription

by

Arthur Machen

April 5, 1911

‘‘Augustus, my love,’’ said Miss Pecksniff, “ask the price of the eight rosewood chairs and the loo table.”

“Perhaps they are ordered already,” said Augustus. “Perhaps they are Another’s.”

“They can make more like them, if they are,” rejoined Miss Pecksniff.

“No, no, they can’t,’’ said Moddle. “It’s impossible.’’

This pleasing dialogue, it will be remembered, took place before the windows of a City furnishing establishment, not far from the Monument.

Miss Charity Pecksniff and her victim, Mr. Moddle (known earlier in the book as the youngest gentleman in the company) are planning the details of their future home.

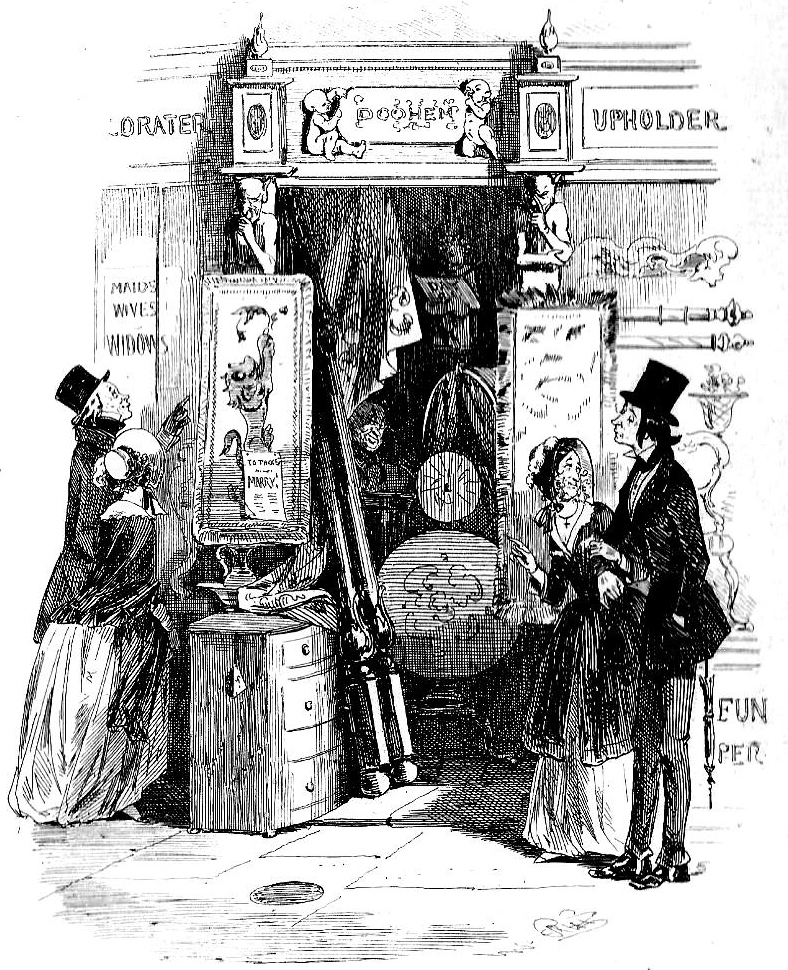

The scene is illustrated by a picture showing Miss Pecksniff and Moddle on one side of the shop and Tom Pinch and his sister Ruth on the other. And I have always been puzzled by one of the inscriptions over the shop, which describes the proprietor as an “Upholder.”

The puzzle was solved the other night by the protests of a gentleman whom I encountered by hazard. His friends had been alluding to him as “Bill, the drunken undertaker”; and he was wounded.

Not by the epithet—it was well deserved—but by the substantive. He protested that he exercised the trade of an Upholder, and refused to be comforted.

___

Swinburne’s handwriting, I see by a paragraph of The Evening News, is ugly, shapeless, and staggering. If that is so, it must form a singular contrast to the script of Edgar Allan Poe, which was curiously uniform and regular.

But Poe’s writing is not at all the kind of calligraphy which one would have expected from the author of strange and wonderful and melodious poems and tales.

Just as Swinburne’s hand lacks all sense of form and beauty, so in Poe’s writing there is nothing of wildness. One would have expected from him a script that reminded one of Arabic or Persian or some such Eastern character, and he wrote his marvels in the careful and well-proportioned text of a well-trained journalist. Personally, I don’t believe in the doctrine of “handwriting an index of character.” Or (perhaps I should put it) you cannot say what particular angle of the character will be reflected on the written page.

In Poe’s writing you see the author of the essay on Cryptograms; Swinburne’s confused and staggering text represents fairly enough his confused and volcanic prose; in neither case does the essential man appear.

___

A reviewer in the Daily Chronicle heads his notice of “Dulce Domum: George Moberley, His Family and Friends” with the words, ‘‘The Daisy Chain”; and I wonder whether he thinks he is hanging garlands of pleasant association about the book.

I am glad to take this opportunity of declaring my deliberate opinion that “The Daisy Chain” is one of the most noxious and detestable books ever written.

Why? Because it causes the Christian Religion to appear as the unhappy, cross-grained invention of an excessively pernickety nursery-governess, temp. 1850.

There is a good old story of Tennyson and this horrible book. The poet was observed to be absorbed in study; he would answer no one; his eyes were glued on the page. At last he gave a sigh of relief. “I see land at last,” he cried. “Harry is to be confirmed, after all.”

___

Messrs. Williams and Norgate are, I am sure, to be congratulated on the issue of their new series, called “The Home University Library.” The first volumes include works on “Parliament,” “Polar Exploration,” “Modern Geography,” “A Short History of War and Peace,” “The Stock Exchange,” “The Socialist Movement,” and “The Evolution of Plants.”

Messrs. Williams and Norgate are, I am sure, to be congratulated on the issue of their new series, called “The Home University Library.” The first volumes include works on “Parliament,” “Polar Exploration,” “Modern Geography,” “A Short History of War and Peace,” “The Stock Exchange,” “The Socialist Movement,” and “The Evolution of Plants.”

These books are, I am certain, most useful and admirable and excellent in every way; but I do not quite see how the following introductory phrase of the publishers is to be justified:—

There is to-day for the first time, standing, as it were, outside the university gates, a great mass of men and women eagerly waiting for the good things of culture to be brought to them.

“The good things of culture” is the phrase that puzzles me. I love and esteem Parliament and Poles—the North Pole and the South Pole—and modern geography, and the Socialist movement, and the Stock Exchange and pistils and stamens as well as any man, though I never could make out why they don’t spell pistils properly.

But I really fail to see how any one of these delightful subjects has the smallest relation to culture in any possible sense of the word. The Stock Exchange is said to be splendid fun and profitable, too, if you have any sort of luck, but what has it got to do with the humane and humanising arts of the old universities?

The association of “bulls” and bears” and “the Kaffir Circus” with the word culture is an acute instance, a reductio ad absurdum of one of the palmary fallacies of modern thought. The fallacy in question? It is this: that information about facts of any kind constitutes “education’’ and “culture.”

___

“The Chancel and the Altar,” by Mr. Harold C. King (Mowbray), is one of those interesting books which explain common objects. Everybody, it is probable, has noticed that most churches are divided into two parts, one of which is the nave, the other the chancel.

It is also probable that very few people have ever asked themselves the reason of this division. Mr. King gives in a few words the main reason:

A church which called its chief service by the name of the ‘‘Holy Mysteries” would naturally be desirous of impressing the idea of a mystery by means of the senses. The protective railing [between sanctuary and people] therefore became . . . a screen.

Previous: A Recipe for the Historical Novel

Next:

Congratulations on – and many thanks for – reaching the 100th installment! And a variously interesting one it is!

The ‘U’ volume of the New English Dictionary (NED) did not appear until March 1926. There I find “Upholder” in the “undertaker” sense illustrated by quotations from Steele, Gay, and Swift in the early 18th century, and one from the Daily Chronicle in 1903. However, it is preceded by the sense (“Obs[olete]”) of “A dealer in small wares or second-hand articles (of clothing, furniture, etc.); a maker or repairer of such things” (pp. 425 col. 3- 426 col. 1) – sadly, with no indication of how the senses are related! (Perhaps by coffin-making?)

While “the Kaffir Circus” is new to me, I find in the NED ‘I-K’ volume (1901) under “Kaffir” that in the plural it is “The Stock Exchange term for South African mine shares” (p. 648 cl. 2).

Mr. Harold C. King’s book looks fascinating – and useful – as does the series edited by Percy Dearmer, “The Arts of the Church”, to which it belongs.

George Moberly rings no bells, but following up his daughter, the author, in the Internet Archive, I find an edition of her book (co-authored with E. F. Jourdain), An Adventure, edited in 1955 by Joan Evans, who notes the popularity of their account of their adventure at Versailles and gives Miss Moberly’s dates as 1846-1937 – which sounds intriguing!

I’m astonished by Machen’s “deliberate opinion that ‘The Daisy Chain’ is one of the most noxious and detestable books ever written” – though I have not read it: for, I have read another of Charlotte M. Yonge’s novels years ago (though I cannot recall which – !), with great enjoyment, and something making me think of her not long ago, I had a look in LibriVox and now have also enjoyed her 14th-c. historical novel, The Lances of Lynwood, and her History of France, and am currently enjoying her Young Folks’ History of Germany.

I’ve also enjoyed the Home University Library books I’ve read so far – Belloc’s The French Revolution being one of this 1911 first batch, and Chesterton’s The Victorian Age in Literature (1913) being one I much enjoyed – as I did whichever version of The Byzantine Empire by Norman H. Baynes it is that I’ve read. I wonder if Machen might find any of those three to have a “relation to culture in any possible sense of the word”? They certainly all seemed to me more than mere “information about facts”.

I enjoyed his reflections on handwriting – one of the delights of my youth was the Dover edition of the manuscript of Dickens’s Christmas Carol (though it was astonishing to think the publisher managed to set the type from it)!

LikeLike

David- As usual, you add so much to these installments with your interesting research. Thanks! Machen often approves or disapproves of a book due to his idiosyncratic set of requirements. Thus far, this is the only mention of “The Daisy Chain” or Yonge that I can recall reading.

LikeLike

I believe I will write a Books Around Machen for publication in the near future in which I will discuss The Daisy Chain.

In the meantime:

“Mr. Machen, meet Mr. C. S. Lewis. Mr. Lewis, Arthur Machen. I believe you differ regarding the merits of Miss Yonge’s novel ‘The Daisy Chain.'”

DN

LikeLike

That would be jolly – thanks!

LikeLike

Looking forward to the proposed article!

LikeLike

All going as I expect, you should have it very soon.

LikeLike