The Weekly Machen

We continue reprinting a series of articles by Arthur Machen on assignment in Belfast. In this column, he finishes an interview that had begun in the previous day’s paper with a number of unnamed Belfast residents. The topic is Home Rule in Ireland and the following anonymous comments grant a snapshot of local opinion during a contentious historical period, including concern of impending violence. The men are prosperous Unionists. However, in the next segment, our enquiring reporter meets a Nationalist.

Belfast’s View of Home Rule:

Proposition That Is Not Businesslike

BIGOTRY REVIVED

by

Arthur Machen

September 26, 1913

The Belfast business men, I said yesterday, object to Home Rule because they can’t afford it. They explained to me what they meant by this.

“You see,” said one of them, “we think that a Nationalist Government would turn out to be very expensive; the New Yorkers find the Tammany government expensive. The money would go in all sorts of ways, the leading Nationalists have a great many friends, and very naturally, something would have to be done for these friends in the way of providing them with comfortable posts. And I daresay, if there wasn’t a post handy and ready for this friend or that friend it would be easy enough to make one. But this would cost a lot of money; and Ulster would have to find it.”

“Why Ulster more than the rest of Ireland?”

“The rest of Ireland, roughly speaking, is agricultural; we in Ulster here are industrial. The Nationalist Government could not tax agriculture and they wouldn’t if they could; so they would have to tax us. Now that’s a prospect we don’t like, and we’re not going to have it. It’s not a business proposition—from the Belfast point of view—and there you have the reason why I object to Home Rule.”

Now the Liberal Press and the Liberal politicians have written and spoken with contemptuous relish of “Ulsteria,” “braggadocio,” “gasconading,” “fire-eating,” and so forth. Well, I can quite conceive a Nationalist saying that the sentiments of my Belfast friend were unkind, but I can’t see that there was anything of a gasconading character in his remarks. And his standpoint is that of many others, of the responsible solid, prosperous Ulster that really counts, that is going to set up its own provisional government—if the Home Rule Bill becomes an Act of Parliament. But my friends did not attempt to deny that the movement had its other side; what one may call the “To hell with the Pope side.”

SOME WHO LOVE VIOLENCE

“Unfortunately,” said one of them, “we have in Belfast a lot of people who love violence for its own sake; they are violent in words and violent in action. They are a very great danger.”

“And there isn’t a penny to choose between the Protestants and the Roman Catholics in this respect,” added another man of affairs; “they are both equally bad. They just like fighting for fighting’s sake.

‘‘And there is this to be remembered. Besides these violent people, there are the bigoted people on our side, and plenty of them. As the old story goes, ‘the Pope may be a very good man, but he isn’t well thought of in Portadown’; and in the small towns and in the villages you will still find a lot of senseless Protestant bigotry and prejudice. It’s a survival from the old traditions, and I’m very sorry that it has survived. Perhaps these people will fight for us, but I hope you understand that we’re not going to fight for them. I think both the bigotry and the bitterness were getting much better in Ulster, gradually fading away in the light of commonsense; but since the production of this wretched Home Rule Bill things are as bad as ever they were.”

“And are you in Belfast afraid that the Roman Catholics will ‘persecute’ you if the Bill is passed?”

“Of course not. In the villages and on the hills, I’ve no doubt there are plenty of people who believe they would be persecuted, but that’s just their ignorance. We are not a bit afraid of being persecuted; but we are afraid of having our pockets picked, as I told you just now.’’ I take it he was right. Very few people are addicted to the sports of persecuting bulldogs and bullying Great Danes.

SENTIMENT COUNTS

“But how about the rest of Ireland?” I asked. “You may say that the Irish of the south and west don’t really want Home Rule, that they only want to be left alone, and get on with their farming. Still, they persist in telling us, through their representatives in Parliament, that they do want Home Rule; do you wish England to say, ‘then want must be your master,’ and leave it at that? Isn’t that treating Ireland outside Ulster as if she were a naughty little girl, who didn’t know what was good for her?”

Then one of the company said that the desire for Home Rule was all a matter of sentiment, and that sentiment was no good, since there was no money in it.

“You can’t run a country on sentiment,” was his summing up.

“I don’t agree with you at all,” said the man who was not afraid that Father O’Flynn would persecute him. ‘‘Sentiment counts for a great deal; men will die for their sentiments sometimes. No; I know the people of the south and west, and I think they’re dear people, and I quite agree that you can’t keep on telling them to run away and play and be good boys. I say let them have Home Rule by all means—so long as they leave the four Protestant counties out of it. Of course, you will understand that I am speaking for myself; many Unionists would disagree with me very strongly indeed. But it’s no good saying that things are going on just as they are in Ireland: something has got to be done. Only, the North is not going to pay for the fun of the South; that’s all. The Belfast man has a profound and stubborn belief in himself and his city and his fellows.”

WANT TO BE LET ALONE

“‘Upon my word,’ one of them said, ‘I believe that if the present Home Rule Bill were passed just as it is in a few years the whole of Ireland would be practically ruled by Ulster; the tail would wag the dog.’

“‘What makes you think so?’

“‘I think so because all the brains of Ireland are up here; the sound, practical businesslike brains, I mean. And in the long run brains always come up on top.’

“‘But you are confirming a common argument of the Liberals. They don’t quite say that all the brains of Ireland are to be found in Belfast: that wouldn’t please their Nationalist friends. But they do say that Ulster would take up a very strong position in the Dublin Parliament, and that it would become a centre for the Conservative policy of Ireland.’

“‘Yes, I know; and I think they are right. We should come out on top, as I say; but it would be a long process and an expensive process, too, and we don’t mean to go through it. We’ve got no ascendancy over the rest of Ireland, and we don’t want it; all we want is to be let alone.'”

Previous: In Belfast To-Day

Next: A Drive Through Belfast

Here is a column copyright by me that the New York C. S. Lewis Society published a few years ago on a book relevant to Machen’s Belfast reportage.

Jack and the Bookshelf No.36

Frank Frankfort Moore’s The Ulsterman

by Dale Nelson

At the rear of this novel by Moore (1855-1931) are 32 pages advertising the books of “Messrs. Hutchinson & Co.” I suppose Lucas Malet’s The Wisdom of Damaris is forgotten, though one idly wonders if it supplied the name of a character in Charles Williams’s The Place of the Lion. Tom Gallon’s It Will Be All Right is about a millionaire. Charles Marriott’s The Unpetitioned Heavens is about an author who misses a love of his own while he supports his widowed sister and her children, “with whom he set up housekeeping at the beginning of his career,” reminding one irrelevantly of the Janie Moore-CSL ménage.

Also advertised is the present, equally forgotten, book itself, miscalled The Ulstermen. “The scene of this new story by Mr. F. Frankfort Moore is wholly laid in Ulster, and all the characters belong to that province, with which Mr. Moore is so familiar. It is not, however, a political novel, but it deals with the life and people of Ulster of to-day as apparently they have never been treated before. The subject in Mr. Moore’s hands will lose none of the humour which it suggests.” Published in 1914, the book cost six shillings, the same as around three dozen other novels listed here.

James Alexander is a 55-year-old Belfast mill-owner, and, like others of his generation, including his wife, speaks a prickly “dialect.” He tricked his brother thirty-some years ago, when that brother, Richard, had set himself to trick his creditors. James prospered. Now, unexpectedly, Richard, who also prospered, in Australia, comes back to Ulster. He admits that he learned an essential business lesson – don’t trust anyone – from his smug brother James, and, while living with him, covertly begins to find ways to avenge himself.

Uncle Dick supports the clandestine love affair of James’s son Ned with a Roman Catholic girl, Kate Power. Richard himself had loved a Catholic girl but had given her up because of Ulster’s intense religious and social divide. Supporting Ned’s romance gratifies Richard’s desire for revenge on his brother, who would detest the idea of his son marrying a “Papish,” and also, one supposes, allows him vicariously to revise his own love-history with what might have been.

Moore’s book surely was intended to appeal to the middle-class women who represented such a large share of the novel-reading public. He provides four young women characters, all of them good-looking, for these feminine readers to identify with. They and their swains speak a bland standard English. Moore likely wasn’t very interested in the portions of the story concerned with their love-business.

Helen, Ned’s sister, complains, “‘People about here are like spies, but they have nothing to talk about …. nothing beyond Home Rule; they read no books, they have no taste in music or in pictures or in anything else that occupies the attention of people elsewhere – in Dublin or London.’” Eligible bachelor Willie Kinghan, who at Oxford was called “the Ulsterman,” strings Helen along – she’s attractive and her father is wealthy – though he’s more interested in Colonel Thurston’s beautiful daughter Minna. (Minna becomes engaged to someone else, and Willie is all set to console himself with Helen, till he encounters her married sister and is frightened off by the vision of what Helen might become.)

Alexander family dinners are marked by James’s repetitive speeches in favor of the Union with England and against Irish Home Rule, and by bickering and lying, as Ned and his brother deceive their domineering father. In 1967, C. S. Lewis’s brother Warren read this novel again. He found it “a burning, bitter, but lifelike picture.” Warren concluded that the rudeness, exasperating inquisitiveness, and bullying (“‘Really for two pins, I’d knock your head off’”) of their father, Albert, were not idiosyncratic, but typical of Ulster heads of families. Warnie copied passages from pages 171-172 and 253, such as the place where Ned Alexander asks if it’s ‘’’any wonder that when we’re treated like this, we sons turn out liars and hypocrites?’”

However, paterfamilias James Alexander shows none of the near-non sequiturs that Warnie and Jack’s “Pudaitabird” father did, and which they documented in a compilation recently published in Seven 32 (2015).

The Ulsterman is set in the fictitious town of Arderry, evidently adjoining Belfast, not the neighborhood with which the Lewis brothers would have been most familiar. The Arderry houses are ugly but sanitary, laid out in monotonous rows, reflecting a community that values usefulness and wealth but not beauty. The opening pages evoke the traditional 12 July lambeg drumming, noting even the appreciation of bloody wrists chafed by the rims of the massive drums. We read of the annual re-enactment of the Battle of the Boyne but don’t get a description of any of the characters actually attending; Ned’s father insists that he go, but he lies about it – complaining to his sister that it’s just “‘rot.’” Just before the uproarious climactic scene at the Alexanders’ dinner table, Ned shows up late to a paramilitary drill. But the novel’s local color passages may be a bit scantier than one would have expected.

The Ulsterman evidently wasn’t Warren’s book, since it appears in the 1969 catalog of C. S. Lewis’s library. CSL’s only known adult venture into realistic fiction, the “Easley Fragment” (published in 2011 in Seven 28), had a Belfast setting, but it doesn’t appear to have been influenced by Moore’s novel.

LikeLike

David Llewellyn Dodds comments:

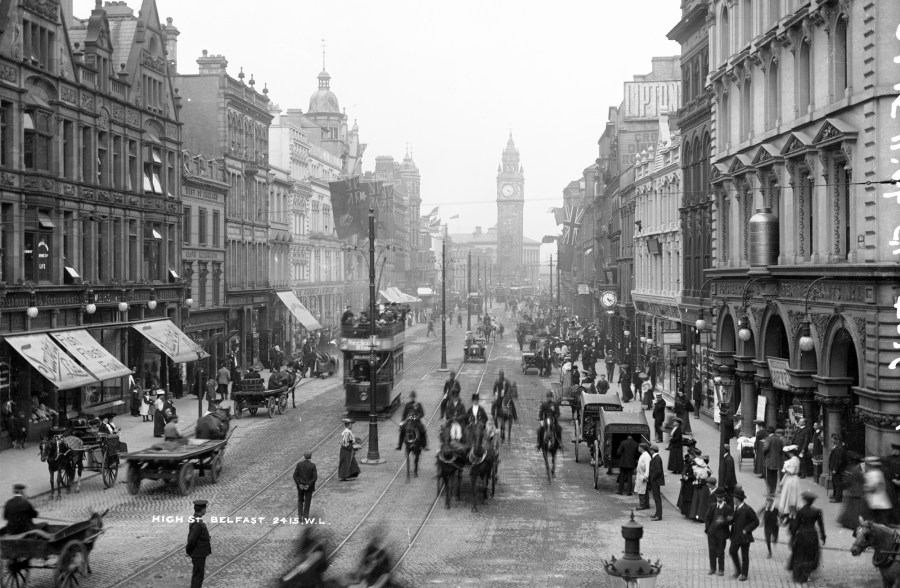

Fun to think of how horsey the Belfast of the young Lewises still was – as that photo shows! (And fascinating how horsey Warren ended up being, and how C.S.L. (or ‘Jack’) seems to have wished to be – for whatever reasons, without becoming…)

Dale Nelson’s review article is welcome, and got me looking further… Interesting that F.F. Moore’s Ulsterman appeared not so very long after Machen’s series – as did his The Truth about Ulster: both in 1914, though I cannot find the former online, and have not tried anything of his (yet?). Checking if there were handy audiobooks of anything by him (without success!), I did just now see (but not yet try) two brief episodes on a YouTube channel called The Weird and the Wonderful, noting he was Bram Stoker’s brother-in-law and author of one collection of short stories, The Other World (1904), and of one fantastic novel, The Secret of the Court: A Romance of Life and Death (1895) – both of which are online. In Belfast by the Sea (2007) sounds interesting: the publisher says it “originally appeared as a series of 61 articles in the ‘Belfast Telegraph’, 1923-4. They comprise Moore’s recollections of Victorian Belfast and Bangor between his childhood in the 1860s and his departure for London in 1892.” But WorldCat doesn’t show a library copy anywhere here in the Netherlands!

LikeLike