The Weekly Machen

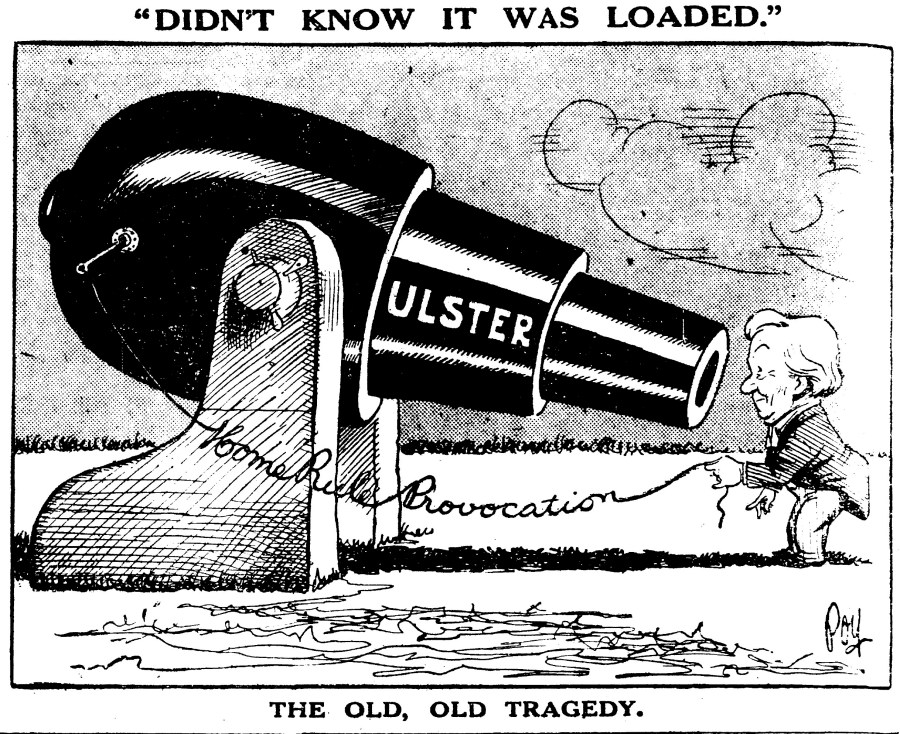

This week, we begin a series reports by Arthur Machen on assignment in Ireland. While this job could not be accurately described as the work of a foreign correspondent, it is the only time Machen was assigned to a story outside the island of Great Britain. With his eye for mystery and wonder, the series has the feel of a man whisked away from his normal existence to a far-off land of enchantment. Though the purported purpose is to cover politics, a subject that mattered little to Machen, our reporter refused to allow current events to hinder his perennial themes. As a topic, the history of Irish Home Rule is too vast to be explored here, however, the following cartoon, which accompanied Machen’s article, vividly portrays the anxiety of the time.

In Belfast To-Day

by

Arthur Machen

September 25, 1913

I got a lesson in pronunciation very soon after I had left the station. I wanted to find a street called the Cornmarket, and I asked a policeman. He looked at me and took a moment’s consideration before he answered, and I was made aware that, like many Londoners, I had slurred a most important letter, and made Cornmarket into something not far from Cawnmahket. And the policeman’s pronunciation approached Corrunmarrket, and he pointed out a landmark on my way by using the adverb “you.” The Belfast accent is a kind of Lowland Scotch, with a certain vigour of aspiration and enunciation that is wholly Irish.

A City of Masons

And having found the Cornmarket and Donegal Square, where the new and splendid Town Hall stands amidst gardens and statues, I found some Belfast people, who told me what they thought about Home Rule and the part that their city was to take in the coming struggle.

At the first glance nothing could have been move bustling, commonplace, or businesslike than Belfast on this fine September morning. Evidently the work of the place has not been frightened away by any terrors of approaching war. In and out of their offices the business men go, stumbling along their broad pavements with a determined air, as of men who have no time to waste on anything but business. At first sight, then, Belfast is any big business town you like to think of: it is only when you look more closely that you seem that there is something curious about the life of the place as it is in these days. I can only say that I felt as if I had strayed into a city where all the citizens were Freemasons, where all were united by a tie not insisted on overmuch, but recognised on every hand.

Acquaintances who in ordinary circumstances would have passed with a hasty nod or the jerk of a hurried finger, stopped for a moment and exchanged a word or two; and those words always related to the one subject. And then there were sudden silences; a man might be speaking his mind freely, when he would catch a certain hint of caution in his friend’s eyes, and would lower his voice or say no more. Someone was present who did not possess the masonic countersign.

In Secret Conclave

It is hardly necessary to specify more particularly the freemasonry which makes voices and silences in the Belfast streets and places of encounter; there is only one thought in this town, and that is the Home Rule Bill, which Belfast is determined to resist with all its strength.

The Ulster Unionist Council was sitting with closed doors in the old Town Hall, and all the town was speculating as to what was passing within, wondering as to dispositions that were being made for the government of the State that was to secede, not from the Empire, but from the Ireland of the Nationalists.

We have most of us been given to understand that the Ulster Unionist has one formula and one only with which to express his dissent from his Roman Catholic countrymen on the great questions of civil and religions polity. This simple phrase of his devotes the Pope to an eternity of torment. I have not yet heard it uttered, though my friends were far from denying that it was to be heard. They said, indeed, that the formula and the men who uttered it represented a very grave and serious danger to their town; but they themselves spoke from a wildly different point of view. They said that as men of business they could not afford Home Rule.

Previous: The Joy of the Circus

Next: In Belfast To-Day

Fascinating – thank you! “The Belfast accent is a kind of Lowland Scotch” – interesting! I’ve certainly heard (I’m not sure how accurately) of the Ulster Plantation as recruited from Scottish Presbyterians (my English Presbyterian ancestors seem in good part convert ‘Episcopalians’ – I’m not sure how or why, or about the Welsh ones’ ‘churchmanship’: the Irish ones were certainly in communion with the Pope). I have no idea which Ulster/Belfast folk in 1913 regarded themselves as ‘Celts’ – who might see in the (now) ‘London Welsh’ Machen a ‘fellow Celt’, or how Machen would regard Church of Ireland folk (such as the Lewises) as ‘fellow Anglicans’. At this date, the nearly-fifteen-year-old C.S. Lewis was just settling into his new school, Malvern College. (Wikipedia tells me “The name Malvern is probably derived from the ancient British moel-bryn, meaning “bare-hill”, the nearest modern equivalent being the Welsh moelfryn (bald hill)” and I think of it as not so far from Wales – though not so close to the Wales of Machen’s youth.) A bit over a year later (on 5 June), Lewis was writing from Malvern to his Belfast friend, Arthur Greeves, “I have here discovered an author exactly after my own heart, whom I am sure you would delight in, W.B. Yeats. He writes plays and poems of rare spirit about our [sic!] old Irish mythology.”

Fascinating ‘Home Rule’ history (which I somehow tend to think of mostly from the days of Trollope and Gladstone) – thanks for the link! The figure in the cartoon is presumably the Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, and his ‘Third Home Rule Bill’, which (saith Wikipedia) “in January 1913 the House of Lords rejected it by 326 votes to 69.” As Oxford undergrad, Lewis wrote Greeves on 9 February 1919 of his fellow-University-College-member, H.P. Blunt, that ” he was at Winchester where he acted a minor part in a production of Yeat’s [sic] ‘On Baile’s Strand’ with the young Asquith [Anthony, fifth son of H.H.] as ‘The Fool’ – some wd. say an appropriate part!”

LikeLike