Editor’s Introduction

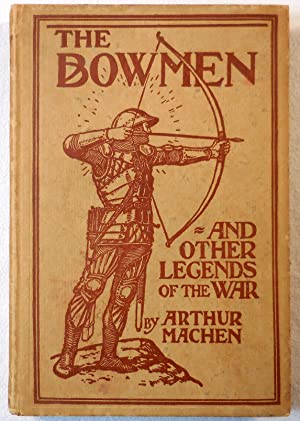

On June 9, 1915, the Evening News published “Karl Heinz’s Diary: The Story of a Battlefield Vision,” a rather brief war story by Arthur Machen. Only two months later, the story reappeared as “The Monstrance” in The Angel of Mons: The Bowmen and Other Legends of the War. In addition to a change of the title, the tale received numerous edits. In the following Machen Study, we offer an integrated text of the two versions, followed by a new essay by scholar David Llewellyn Dodds, a contributor to the Darkly Bright critical edition of THE TERROR.

PART ONE

The Monstrance / Karl Heinz’s Diary Composite Text

Epigraph from Karl Heinz’s Diary:

Then it fell out in the sacring of the Mass that right as the priest heaved up the Host there came a beam redder than any rose and smote upon it, and then it was changed into the shape of a Child having his arms stretched forth, as he had been nailed upon the Tree. — Old Book

Epigraph from The Monstrance:

Then it fell out in the sacring of the Mass that right as the priest heaved up the Host there came a beam redder than any rose and smote upon it, and then it was changed bodily into the shape and fashion of a Child having his arms stretched forth, as he had been nailed upon the Tree. — Old Romance

So far things were going very well indeed. The night was thick and black and cloudy, and the German force had come three-quarters of their way or more without an alarm. There was no challenge from the English lines; and indeed the English were being kept busy by a high shell-fire on their front. This had been the German plan; and it was coming off admirably. Nobody thought that there was any danger on the left; and so the Prussians, writhing on their stomachs over the ploughed field, were drawing nearer and nearer to the wood. Once there they could establish themselves comfortably and securely during what remained of the night; and at dawn the English left would be hopelessly enfiladed — and there would be another of those movements which people who really understand military matters call “readjustments of our line.”

So far things were going very well indeed. The night was thick and black and cloudy, and the German force had come three-quarters of their way or more without an alarm. There was no challenge from the English lines; and indeed the English were being kept busy by a high shell-fire on their front. This had been the German plan; and it was coming off admirably. Nobody thought that there was any danger on the left; and so the Prussians, writhing on their stomachs over the ploughed field, were drawing nearer and nearer to the wood. Once there they could establish themselves comfortably and securely during what remained of the night; and at dawn the English left would be hopelessly enfiladed — and there would be another of those movements which people who really understand military matters call “readjustments of our line.”

The noise made by the men creeping and crawling over the fields was drowned by the cannonade, from the English side as well as the German. On the English centre and right things were indeed very brisk; the big guns were thundering and shrieking and roaring, the machine-guns were keeping up the very devil’s racket; the flares and illuminating shells were as good as the Crystal Palace in the old days, as the soldiers said to one another. All this had been thought of and thought out on the other side. The German force was beautifully organised. The men who crept nearer and nearer to the wood carried quite a number of machine guns in bits on their backs; others of them had small bags full of sand; yet others big bags that were empty. When the wood was reached the sand from the small bags was to be emptied into the big bags; the machine-gun parts were to be put together, the guns mounted behind the sandbag redoubt, and then, as Major Von und Zu pleasantly observed, “the English pigs shall to gehenna-fire quickly come.” *

* {Editor’s Note: The preceding paragraph is unique to “The Monstrance.”}

The major was so well pleased with the way things had gone that he permitted himself a very low and guttural chuckle; in another ten minutes success would be assured. He half turned his head round to whisper a caution about some detail of the sandbag business to the big sergeant-major, Karl Heinz, who was crawling just behind him. At that instant Karl Heinz leapt into the air with a scream that rent through the night and through all the roaring of the artillery. He cried in a terrible voice, “The Glory of the Lord!” and plunged and pitched forward, stone dead. They said that his face as he stood up there and cried aloud was as if it had been seen through a sheet of flame.

“They” were one or two out of the few who got back to the German lines. Most of the Prussians stayed in the ploughed field. Karl Heinz’s scream had frozen the blood of the English soldiers, but it had also ruined the major’s plans. He and his men, caught all unready, clumsy with the burdens that they carried, were shot to pieces; hardly a score of them returned. The rest of the force were attended to by an English burying party. According to custom the dead men were searched before they were buried, and some singular relics of the campaign were found upon them, but nothing so singular as Karl Heinz’s diary.

He had been keeping it for some time. It began with entries about bread and sausage and the ordinary incidents of the trenches; here and there Karl wrote about an old grandfather, and a big china pipe, and pinewoods and roast goose. Then the diarist seemed to get fidgety about his health. Thus:

April 17. — Annoyed for some days by murmuring sounds in my head. I trust I shall not become deaf, like my departed uncle Christopher.

April 20. — The noise in my head grows worse; it is a humming sound. It distracts me; twice I have failed to hear the captain and have been reprimanded.

April 22. — So bad is my head that I go to see the doctor. He speaks of tinnitus, and gives me an inhaling apparatus that shall reach, he says, the middle ear.

April 25. — The apparatus is of no use. The sound is now become like the booming of a great church bell. It reminds me of the bell at St. Lambart on that terrible day of last August.

April 26. — I could swear that it is the bell of St. Lambart that I hear all the time. They rang it as the procession came out of the church.

The man’s writing, at first firm enough, begins to straggle unevenly over the page at this point. The entries show that he became convinced that he heard the bell of St. Lambart’s Church ringing, though (as he knew better than most men) there had been no bell and no church at St. Lambart’s since the summer of 1914. There was no village either; the whole place was a rubbish-heap.

Then the unfortunate Karl Heinz was beset with other troubles.

May 2. — I fear I am becoming ill. To-day Joseph Kleist, who is next to me in the trench, asked me why I jerked my head to the right so constantly. I told him to hold his tongue; but this shows that I am noticed. I keep fancying that there is something white just beyond the range of my sight on the right hand.

May 3. — This whiteness is now quite clear, and in front of me. All this day it has slowly passed before me. I asked Joseph Kleist if he saw a piece of newspaper just beyond the trench. He stared at me solemnly — he is a stupid fool — and said, “There is no paper.”

May 4. — It looks like a white robe. There was a strong smell of incense to-day in the trench. No one seemed to notice it. There is decidedly a white robe, and I think I can see feet, passing very slowly before me at this moment while I write.

There is no space here for continuous extracts from Karl Heinz’s diary. But to condense with severity, it would seem that he slowly gathered about himself a complete set of sensory hallucinations. First the auditory hallucination of the sound of a bell, which the doctor called tinnitus. Then a patch of white growing into a white robe, then the smell of incense. At last he lived in two worlds. He saw his trench, and the level before it, and the English lines; he talked with his comrades and obeyed orders, though with a certain difficulty; but he also heard the deep boom of St. Lambart’s bell, and saw continually advancing towards him a white procession of little children, led by a boy who was swinging a censer. There is one extraordinary entry: “But in August those children carried no lilies; now they have lilies in their hands. Why should they have lilies?”

It is interesting to note the transition over the border line. After May 2 there is no reference in the diary to bodily illness, with two notable exceptions. Up to and including that date the sergeant knows that he is suffering from illusions; after that he accepts his hallucinations as actualities. The man who cannot see what he sees and hear what he hears is a fool. So he writes: “I ask who is singing ‘Ave Maria Stella.’ That blockhead Friedrich Schumacher raises his crest and answers insolently that no one sings, since singing is strictly forbidden for the present.”

A few days before the disastrous night expedition the last figure in the procession appeared to those sick eyes.

The old priest now comes in his golden robe, the two boys holding each side of it. He is looking just as he did when he died, save that when he walked in St. Lambart there was no shining round his head. But this is illusion and contrary to reason, since no one has a shining about his head. I must take some medicine.

Note here that Karl Heinz absolutely accepts the appearance of the martyred priest of St. Lambart as actual, while he thinks that the halo must be an illusion; and so he reverts again to his physical condition.

The priest held up both his hands, the diary states, “as if there were something between them. But there is a sort of cloud or dimness over this object, whatever it may be. My poor Aunt Kathie suffered much from her eyes in her old age.”

One can guess what the priest of St. Lambart carried in his hands when he and the little children went out into the hot sunlight to implore mercy, of God and of the enemies of God,* while the great resounding bell of St. Lambart boomed over the plain. Karl Heinz knew what happened then; they said that it was he who killed the old priest and helped to crucify the little child against the church door. The baby was only three years old. He died calling piteously for “mummy” and “daddy.”

And those who will may guess what Karl Heinz saw when the mist cleared from before the monstrance in the priest’s hands. Then he shrieked and died.

* {Editor’s Note: This phrase was deleted for the publication of “The Monstrance.”}

PART TWO

PART TWO

by David Llewellyn Dodds

In June 1981, Raider of the Lost Ark premiered, building to the spectacular scene of the Nazis opening the Ark of the Covenant, with what its scriptwriter described as “A light so bright […] that there is nothing in our world to compare”. Almost exactly 66 years earlier, Arthur Machen published the first version of this story, with something analogous, but subtler and weightier.

If its use of diary extracts has fictional antecedents going back at least to Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year (1722), it is also preceded by polemical works published earlier in 1915, notably German atrocities from German evidence and its sequel, How Germany seeks to justify her atrocities, by the French mediaevalist Joseph Bédier, with photographed excerpts from German soldiers’ diaries translated and discussed. And Lambertus Mokveld later published a vivid account of a Dutch urban procession antedating Machen’s fictional village one: from the beginning of the war when, on 7 August, within earshot of the artillery over the border in Belgium, “nearly the whole population of Maastricht, with all their temporary guests, formed an endless procession and went to invoke God’s mercy by the Virgin Mary’s intercession. They went to Our Lady’s Church, in which stands the miraculous statue of Sancta Maria Stella Maria […] men, women, and children, all praying aloud, with loud voices beseeching: ‘Our Lady, Star of the Sea, pray for us’”. (1) Machen’s village name presumably recalls real place names, like the St. Lambert Wood through which German troops advanced on 5-6 August 1914 and the bridge of Val-St.-Lambert across which Belgian troops retreated on 14 August. As one turns to Karl Heinz’s experiences, it is worth recalling that 6 August is the Feast of the Transfiguration, and considering that Machen may well have been familiar with Jan van der Pille’s 1674 Monstrance with the Transfiguration depicted on its foot, added to the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1874. (2)

Karl Heinz’s mysterious experiences in fact begin some seven weeks before 31 May, the translation Feast of St. Lambert, who in some accounts was martyred together with his two young nephews in the house to which site St. Hubert later translated his relics, building the church around which the city of Liège grew up. In Karl Heinz’s developing experiences, sight followed hearing, after hearing had grown definite in relation to what he calls “that terrible day of last August.” And they have become ever more definitely liturgical experiences – in relation to a “procession” on that day. “Smell of incense” is added to clear sight first of a white robe, then feet under it as well. Machen condenses, reporting the sergeant “heard the deep boom of St. Lambart’s bell, and saw continually advancing towards him a white procession of little children”. He adds “one extraordinary entry: ‘But in August those children carried no lilies; now they have lilies in their hands. Why should they have lilies?’” Karl Heinz’s continual experience is not a memory. It is related but distinct. Machen provides a mystery: why does Karl Heinz not understand the difference? Ignorance, or evasion (however conscious or not)?

Though continual, the experience develops ever further. To sound is added recognizable articulate singing: “I ask who is singing ‘Ave Maria Stella.’” Another mystery: how does he know this hymn, but not the significance of lilies? Then, visual additions: “The old priest now comes in his golden robe, the two boys holding each side of it.” With an explicit detail as to why it was “that terrible day”: “He is looking just as he did when he died”. And a further mystery: “save that when he walked in St. Lambart there was no shining round his head. But this is illusion and contrary to reason, since no one has a shining about his head.” Here, however, is no question, but an active rejection: he ignores apparent evidence to presume a ‘logical’ conclusion. Sloppiness, or evasion?

Another aspect of development: “The priest held up both his hands, the diary states, ‘as if there were something between them. But there is a sort of cloud or dimness over this object, whatever it may be.’” A further difference between then and now, like the lilies and shining, though Karl Heinz should be able to remember what was “between them” on “that terrible day”, and make a mental comparison. This penultimate stage seems to have been protracted for a “few days”.

More and more is added to what Karl Heinz heard and “saw continually” during these seven weeks. “At last he lived in two worlds.” How does this come about? It seems a mystery of psychology, but also of more than psychology. Is there some kind of interaction in the progress from seeking physiological explanations, to “fancying”, to becoming “convinced” as to what he heard and saw? And a resistance to be worn down?

Then, a report: “they said” – presumably the same “they” who “were one or two out of the few who got back to the German lines”, after they had seen “his face […] as if it had been seen through a sheet of flame.” Had these fellow-soldiers been with him all the time? For “they said that it was he who killed the old priest and helped to crucify the little child against the church door.” Acting alone, then “helped”. They report him a deliberate, blasphemous killer – and torturer – of Christian civilian non-combatants: as sergeant, distinctly responsible. Unlike the diaries Bédier cites, there has been no word of any of this quoted from his diary: nothing more definite than that adjective “terrible”. No self-justifications, no remorse, no gloating. Machen, in the character of journalist-narrator, has provided probable evidence for why Karl Heinz suddenly (in whatever language) “cried in a terrible voice, ‘The Glory of the Lord!’”

Machen ends, “those who will may guess what Karl Heinz saw when the mist cleared from before the monstrance in the priest’s hands.” But he has also added an epigraph. It seems an analogue to two passages from Malory’s account of the Quest for the ‘Sangreal’ or Holy Grail (Book XVII, Chapter XX), combined. These passages give descriptions of what the three knights who Achieve the Grail see at a Grail Mass in Carbonek, first: “at the lifting up there came a figure in likeness of a child, and the visage was as red and as bright as any fire, and smote himself into the bread, so that they all saw it that the bread was formed of a fleshly man”; and later: they looked “and saw a man come out of the Holy Vessel, that had all the signs of the passion of Jesu Christ, bleeding all openly”. Machen seems to suggest the vision in the epigraph is what Karl Heinz saw, at last.

In Malory, that “man” then bids Galahad to carry the Holy Vessel to “the city of Sarras in the spiritual place” and he will see more. There (Chapter XXII), Joseph of Arimathea celebrates Mass and says to Galahad “thou shalt see that thou hast much desired to see. And then he began to tremble right hard when the deadly flesh began to behold the spiritual things. Then he held up his hands toward heaven and said: Lord, I thank thee, for now I see that that hath been my desire many a day. Now, blessed Lord, would I not longer live, if it might please thee, Lord”, and soon after Galahad received “Our Lord’s body”, “his soul departed to Jesu Christ”.

Though a miles – the Latin word for both soldier and knight – Karl Heinz is not like Galahad. In his time of visionary experience, he is more like Saul on the road to Damascus, and could say like him “I persecuted this way unto death” (Acts 22:4), though his seeing and hearing last longer, and there is no record of him hearing “I am Jesus Whom thou persecutest” (9:5, 22:8, 26:15). Machen does not venture to say if his confession or proclamation of “The Glory of the Lord” is a faithful one, or not. Neither his vision of the innocent martyrs with their lilies (characteristically substituted for the martyr’s palm of victory) nor of the martyred priest with his halo in the heavenly procession bring him quickly to that cry. In contrast to St. Paul’s experience, or that attributed in late accounts to St. Hubert, (3) his is more like Francis Thompson’s account of “The Hound of Heaven” in its ineluctability and crescendo. In any case, the Providential effect of the long visionary process with his cry in his hour of death coming when it does, is the temporal salvation of the men of “the English left” flank, giving them the opportunity thoroughly to defeat the German attackers. Worth noting, too, is that the hymn Karl Heinz hears in May – and presumably heard the previous August – “Ave Stella Maria”, in asking for intercessory prayer, includes the petitions, “Solve vincla reis, / profer lumen cæcis,” (“Loosen the chains of the guilty, / Send forth light to the blind,”): prayers of his sanctified victims not least for him.

To the revised version of the story, Machen adds the frustrated expectation of “Major Von und Zu” who had “pleasantly observed, ‘the English pigs shall to gehenna-fire quickly come.’” This may represent a subtle play with a verse from the ‘Song of the Three Children’ in Daniel 3:66 (AV ‘Apocrypha’), following that allusively made in “The Bowmen” when he wrote of “this seven-times-heated hell”: “O Ananias, Azarias, and Misael, bless ye the Lord: praise and exalt him above all for ever: for he hath delivered us from hell, and saved us from the hand of death, and delivered us out of the midst of the furnace and burning flame: even out of the midst of the fire hath he delivered us.”

In The Great Return, Machen would go on to write of benefactions by means of a great bell and of the healing of enmities, both in relation to the Sangraal. And in The Terror he would make more elaborate use of diary entries related to mysterious liturgical experiences.

NOTES

1 Lambertus Emanuel Mokveld, The German Fury in Belgium: Experiences of a Netherland Journalist during Four Months with the German Army in Belgium, translated by C. Thieme, with a Preface by John Buchan (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1917), page 17.

2 Monstrance. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O377018/monstrance/ It is possible that Machen also knew of Jan Petrus Verschuylen’s 1839 Monstrance in St. Paul’s Church in Antwerp, which depicts the conversion of St. Paul on the foot. “The fact that his sword (which disappeared after 1972) has been partly drawn out of its sheath, shows how much he was ‘still breathing murderous threats against the disciples of the Lord’ (Acts 9:1).” https://www.sintpaulusantwerpen.be/en/art-history/art-collection/treasury/

3 In his 1910 “St. Hubert” article in the Catholic Encyclopedia, C.F. Wemyss Brown writes “As he was pursuing a magnificent stag, the animal turned and, as the pious legend narrates, he was astounded at perceiving a crucifix between its antlers, while he heard a voice saying: ‘Hubert, unless thou turnest to the Lord, and leadest an holy life, thou shalt quickly go down into hell’. Hubert dismounted, prostrated himself and said, ‘Lord, what wouldst Thou have me do?’ He received the answer, ‘Go and seek Lambert, and he will instruct you.’ Accordingly, he set out immediately for Maastricht, of which place St. Lambert was then bishop. The latter received Hubert kindly, and became his spiritual director. Hubert, losing his wife shortly after this, renounced all his honors and his military rank”. This episode was apparently adapted from the legend of St. Eustace. In Caxton’s translation of The Golden Legend, which has no Life of St. Hubert, the Life of St. Eustace includes “as he beheld and considered the hart diligently, he saw between his horns the form of the holy cross shining more clear than the sun, and the image of Christ, which by the mouth of the hart, like as sometime Balaam by the ass, spake to him, saying: […] wherefore followest me hither? I am appeared to thee in this beast for the grace of thee. I am Jesu Christ, whom thou honourest ignorantly, thy alms be ascended up tofore me, and therefore I come hither so that by this hart that thou huntest I may hunt thee. And some other say that this image of Jesu Christ which appeared between the horns of the hart said these words.” St. Hubert’s Feast is on 30 May, but on account of this episode, his translation Feast of 3 November has been better known to popular imagination.

Oh I just remembered this story. It was in a paperback of ghost stories I read in my early teens. This one was a bit obscure for me.

I’d always assumed that the soldier saw his own severed head being held by the ghostly priest … but I see you have a much more in-depth explanation.

LikeLike