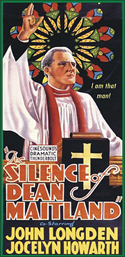

The Silence of Dean Maitland by Maxwell Gray

Dale Nelson

In a 9 October 1908 “Literary Week” column for T. P.’s Weekly, Arthur Machen, in passing, mentions The Silence of Dean Maitland as a favorite of his. (The column is reprinted in Darkly Bright’s collection Mist and Mystery.) Machen mentions it in company with another little-known work and with Hawthorne’s famous Scarlet Letter.

In a 9 October 1908 “Literary Week” column for T. P.’s Weekly, Arthur Machen, in passing, mentions The Silence of Dean Maitland as a favorite of his. (The column is reprinted in Darkly Bright’s collection Mist and Mystery.) Machen mentions it in company with another little-known work and with Hawthorne’s famous Scarlet Letter.

The Silence of Dean Maitland was published in the late Victorian period, the same time that Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, and Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, were published. Gray’s book appeared in 1886, shortly before Machen began to publish some of his most famous stories. Because The Silence of Dean Maitland describes the guilty consequences of an illicit sexual relationship – in a completely non-prurient way – Machen’s association of this novel with Hawthorne’s is entirely appropriate. To that element is added the mystery of a killing and the severe punishment borne by an innocent man, a friend of the culprit.

Unlike the famous thrillers by Gray’s peers Stevenson and Haggard, Gray’s novel might seem, to some readers, to be “slow-moving,” but I had no urge to drop it.

In its first 50 pages and more, it seems to be a fairly realistic novel of rural life, with leisurely narration of rustics prosing away in the village tavern, two pretty young women talking in a cosy parlor, a scene in which one of them calms an overexcited horse at the smithy, &c. If I’d just picked it up and asked myself if the Machen who did not care for the fiction of George Eliot would have liked it, I would have guessed he would not.

About 100 pages further on, yes, The Silence of Dean Maitland gripped me, with characters who interested me and whom I cared about. By this point the author is making real to the reader the way that guilt and secrecy may flow beneath superficial good behavior and also within someone who seriously aspires after rightness of life. For sure the author is interested in more than working out a plot. At this point in the reading, if I were to invoke a well-known novelist, I might have said it’s as if Anthony Trollope set himself to tell a story of an illicit sexual entanglement that, suppressed by the parties involved, catches the innocent too in its consequences, and had employed a bit of the ingenuity of Wilkie Collins. (In fact, there’s what has to be an allusion to Collins’s anthology-plum, “A Terribly Strange Bed.”

The protagonist finds himself that agonizing state wherein (Part One, Chapter 16) he reflects: “Better, far better, it would have been to have taken the step he meditated at such dreadful cost to himself at the very first, before this fearful coil wound itself round [his innocent friend]; every moment’s delay made it worse, and now there was scarcely room for fate to alter things.” But he can’t bring himself to come clean. I don’t know if writing today, given our largely post-Christian literary culture, very often deals with such issues of conscience. Yet those issues can make for memorable fiction.

If I were writing a critical review of the novel, I would develop a critique of the courtroom scene. It’s good but a great author could’ve written it better — but it’s good enough that I had not the least temptation to stop reading.

After that episode, The Silence of Dean Maitland continued to please. We have the adventure here of the escape of an innocent man accused of a killing. Since my wife and I often watch teleplays of David Janssen’s The Fugitive, I could be expected to enjoy it! The novel is said to be melodramatic — fine, but the account of the fugitive’s plight is surely plausible. In fact, he is recaptured and sentenced to worse incarceration than he had before. At this point in my reading, I decided that, unless the book fell away from the level it had so far attained, it is indeed a neglected classic.

The guilty dean – in the public eye – thrived not just as a worldly success, with a nice ecclesiastical living, but as a preacher of uncommon power. But his inner brokenness will become manifest at last.

When I finished The Silence of Dean Maitland, I asked myself about its achievement. I would say the final 75 pages or so were certainly better than just adequate, but maybe didn’t confirm the idea that here we truly have a “neglected classic.” Emphatically, The Silence of Dean Maitland is a good Victorian novel that I am glad to have read. Will I read it again? I’m not sure. I’m glad that Arthur Machen’s remark put me on to it and I like Machen a bit the better because he thought so well of it. I think that speaks well for his values.

When I finished The Silence of Dean Maitland, I asked myself about its achievement. I would say the final 75 pages or so were certainly better than just adequate, but maybe didn’t confirm the idea that here we truly have a “neglected classic.” Emphatically, The Silence of Dean Maitland is a good Victorian novel that I am glad to have read. Will I read it again? I’m not sure. I’m glad that Arthur Machen’s remark put me on to it and I like Machen a bit the better because he thought so well of it. I think that speaks well for his values.

Incidentally, “Maxwell Gray” is a pseudonym. The author was Mary Gleed Tuttiett (1846-1923). A surgeon’s daughter, her Isle of Wight background comes through in Dean Maitland’s story. She was a private person who suffered from lung weakness. After overlooking Tuttiett for decades, the Dictionary of National Biography caught up with her, saying of Silence, “Many doubted whether it should have been written, since it placed crime at the heart of the church. It also shattered the pastoral idealization of the countryside, based on her own experience of rustic life. With notoriety came demand and Maxwell Gray’s contribution to Victorian sensation fiction sold in its thousands, while making her widely known.” Yet a bid on her behalf to the Royal Literary Fund – she was caring for her parents – was co-sponsored by the wife of the Bishop of Ely.

Might one place Hawthorne’s and Tuttiett’s novels favorably in a ‘genre’ including (to name two books I have not yet read) Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris (1831) and Sinclair Lewis’s Elmer Gantry (1927)?

LikeLike

I remember a paper by the late Gisbert Kranz about Priests in Charles Williams’s fiction (I think it may be online somewhere in the issues of the Quarterly at the Charles Williams Society website), but trying Clergy in literature as a search-term phrase at the Internet Archive just now, I did not find anything with a really broad scope except Leland and Philip Ryken and Todd Wilson’s Pastors in the Classics: Timeless Lessons on Life and Ministry from World Literature (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2012) (under “Texts to Borrow”) and Heinrich Schacht’s little 1904 dissertation, Der gute Pfarrer in der englischen Literatur bis zu Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield. The only Elizabeth Goudge novel the former includes is The Dean’s Watch, which I thoroughly enjoyed, but thinking of flawed clergymen not illustrating one of the Seven Deadly Sins (so to put it), I first thought of characters in her novels The Scent of Water and The White Witch.

LikeLike

It finally occurred to me to check Rykens & Wilson!: sadly, the search function got no results for Gray or Maitland.

LikeLike

I just enjoyed Bruce Marshall’s Father Malachy’s Miracle (1931) albeit in Dutch translation (but found it scanned in the Internet Archive in English), which is full of priests, a couple bishops, a cardinal, and assorted Anglican and Protestant clergy – and it struck me how full of clergy Bruce Marshall’s novels seem to be (though I have only read two others, The Fair Bride (about the Spanish Civil War) and A Thread of Scarlet), and indeed studies of various clergymen.

LikeLike