The Weekly Machen

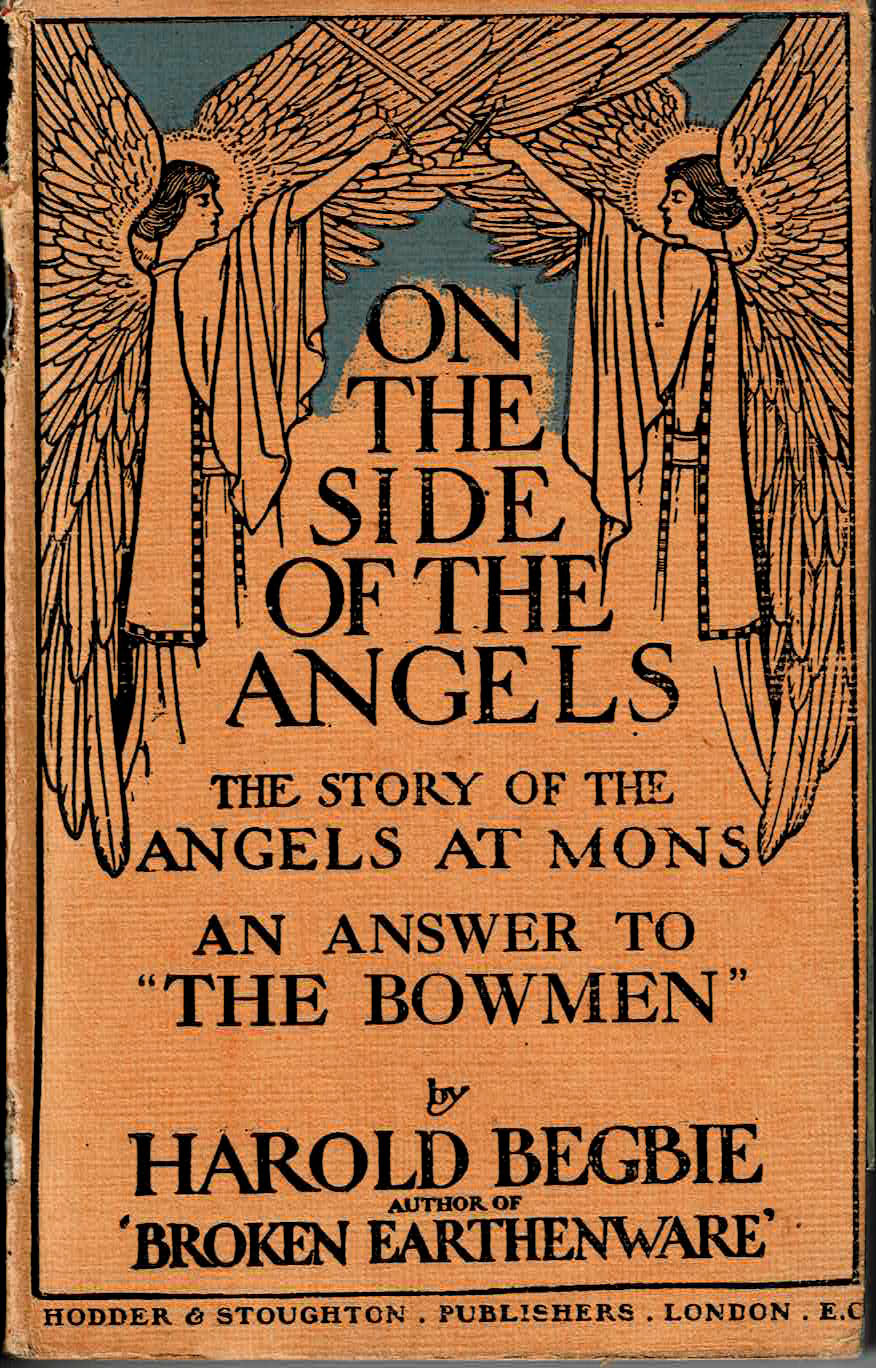

Though mostly forgotten today, Harold Begbie was a popular author in early twentieth-century Britain. During the Angel of Mons controversy, Begbie joined the fray after being commissioned to write a little book to serve as a counter-narrative to Arthur Machen’s claims in the Evening News. On the Side of the Angels: A Reply to Arthur Machen proved quite popular and sold through four editions. However, it was a haphazard production which consisted of recycled anecdotes posing as evidence, a characteristic which frustrated Machen. In later editions, Begbie was forced to reedit his work after multiple errors and fabrications were exposed.

For his part, Machen, who knew Begbie personally, claimed that Begbie did not believe a word of what he wrote in On the Side of the Angels. Today, this opportunistic volume is difficult to find, but it is included in Richard J. Bleiler’s excellent book, The Strange Case of the Angels of Mons (McFarland, 2015).

That Angels:

Mr. Arthur Machen Replies to the Reply to “The Bomwen”

by

Arthur Machen

September 9, 1915

In the following article Mr. Arthur Machen, now famous as the author of “The Bowmen”—which is selling at the rate of 3,000 a day,* and is one of the greatest literacy successes of the war—replies to Mr. Harold Begbie.

Mr. Begbie to-day publishes a book entitled “On the Side of the Angels,” in which he defends the claims that there was actually and literally angelic interposition during the retreat from Mons.

Mr. Machen examines the various arguments. He takes the view, to quote “Pickwick,” that “what the soldier said was not evidence”; or rather that the scanty evidence of soldiers adduced by Mr. Begbie is not strong enough to support the author’s case.

* Editor’s Note: This curious claim of sale numbers is impossible to verify and difficult to square with the purported number of copies printed. See Selling the Angels

____

It is my sincere hope that Mr. Harold Begbie will extend a certain indulgence to me if, in commenting on his “On the Side of the Angels,” I refrain from discussing certain topics which he has elaborated in the course of his book.

It is my sincere hope that Mr. Harold Begbie will extend a certain indulgence to me if, in commenting on his “On the Side of the Angels,” I refrain from discussing certain topics which he has elaborated in the course of his book.

These are: My own failure to realise human suffering, my “rather sinister genius,” the judgement of the Christ on the “posturings and abasements of the Jewish temple,” my “pitiable depths,” my paltriness, my pomposity, and the views of the author on God, Life, and Immortality. Some of these topics are of great importance; others are, I think, of minor consequence; none is germane to the point at issue between Mr. Begbie and myself.

If I had been writing a month ago, I could have stated that point very clearly and very simply. I should have said, “with my hand on my heart,” as Mr. Begbie puts it, that I did not believe that there was one scrap or jot or tittle of real evidence to support the rumour of supernatural or supernormal interference on behalf of the British Army during the retreat from Mons. That was my position up to the publication of “The Bowmen,” but a day or two later The Daily Mail interviewed a Lance-Corporal, who declared that he had seen a vision in the day “on or about August 28,” 1914. The corporal said that he saw three golden shining shapes in mid-air; and the shape in the centre, which was larger than the others, had “what looked like outspread wings.” This, I think, is real evidence, as distinguished from gossip and hearsay.

There was, also, an affidavit of angels taken by a justice of the peace from the lips of one Private Cleaver. “I myself was at Mons, and saw the Vision of Angels.” But the justice of the peace was honest and careful enough to make some inquiries about the private, and it turned out that Cleaver did not leave these shores for the front till the retreat from Mons was ended. Mr. Begbie scorns “police-court methods” in investigation; but I think that this moral tale of Private Cleaver’s affidavit should make him hesitate in condemning common honesty and common carefulness.*

* Editor’s Note: See Selling the Angels for more on Private Cleaver.

The Omission That Matters

It would have been, perhaps, better, if Mr. Begbie had added to his account of Private Cleaver’s affidavit the little circumstance that the private was in Chester—or at all events, “somewhere in England”—till after the end of the Mons retreat. But this, after all, is a matter of taste.

But as to the lance-corporal’s evidence: what do I make of it? Quite frankly, I do not know what to make of it. I incline to think that the corporal and his fellow seers of the vision, being in a state of the extremest exhaustion, became subject to hallucination. But I only think this; I suspend my final judgment for further and fuller evidence.

Such evidence I had hoped to find in “On the Side of the Angels,” but I have not found it. I find instead the repetition of the gossip and hearsay and third-hand statements of many months past. This (to me) is of no value. Thus:

The Rev. O. G. Monck, M.A., Prebendary of Wells and Rural Dean of Martock,* has received a letter from a personal friend . . . in which the following passage occurs:—“The account I sent you was taken down from the lips of a wounded man in hospital in London by one of Sir H.’s sisters who was working there. She knew the man well, etc., etc.

* Editor’s Note: Here is an example of Begbie’s carelessness, or perhaps dishonesty, as no Prebendary of Wells by this name existed. See Bleiler, page 33.

Oddly enough, Mr. Begbie does not give us this famous account: but I will confess openly that I should regard any statement thus produced, as valueless. A (Prebendary Monck) knows B (anonymous) who (presumably) knows C (anonymous nurse) who is sister to “Sir H.,” and C took down a statement from unnamed D—the wounded man. Mr. Begbie has plenty of “evidence” of this nature. He appears to find it good enough for him. I do not envy him; I rather marvel; and I adhere to what Mr. Begbie calls police-court methods. Certainly the object of police-court methods is to ascertain the truth; and this object seems to me a harmless one.

A Leader Who Misleads

There are further points on which I disagree from Mr. Begbie. I have seen a vision myself, but I am very far from being expert in such matters, and, if I may say so, I am inclined to think that Mr. Begbie knows less about visions than I do—if that be possible. But on page 24 of his book he certainly says that “a vision is no palpable and tangible thing. It flashes into sight and disappears.” And then, on page 36, Mr. Begbie is examining the lance-corporal of The Daily Mail interview:

I asked him how he knew that the vision lasted forty-five minutes. “That’s wrong, that is,” he said. “I told Miss Wilson it was somewhere about that, but I know exactly how long it lasted: it was thirty-five minutes.

“It flashes into sight and disappears!”

And, later in the book, the author quotes from the proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research certain histories of visions. He will perceive, if he refer to these, that in no one instance was the vision of the dead an affair of flashing into sight and disappearing. So Mr. Begbie is misleading here, and he is misleading too when he says that there is a definite military order that soldiers are not to speak of their experiences at the front for purposes of publication until after the war. The hundreds of soldiers’ letters that have been printed should inform him better, and also the affidavit of Private Cleaver, which he himself quotes. He is misleading again when he says that “only a remnant” of Expeditionary Force came out of the “furnace of Mons” with their lives. I feel certain—though I write without the figures—that up to September 5th, 1914, the Force had not lost 5,000 killed out of its 70,000.

Too Much of a Difference

Then, as to Miss Campbell’s soldiers who knew that their apparition was St. George because it was exactly like the figure on the sovereign. I have pointed out that their apparition of a bare-headed figure in golden armour is not in the least like the image of the coinage, which depicts a helmeted man without any armour or clothing save a short cape. Mr. Begbie asks: “Is not the very inaccuracy rather a proof of the story’s genuineness?” No, I really do not think it is. If there were a man whom I only met at the swimming-baths, whom I only knew in exiguous bathing costume; and if I said that I had seen a vision in Hyde Park of a man in the full dress uniform of a field marshal; and if I said further that I immediately recognised this vision as “Jones of the baths” from the tout ensemble—the phrase of Miss Campbell’s—well, no, I do not think that the “very inaccuracy” would be a proof of the story’s genuineness, or—shall we not rather say?—authenticity.

I am sorry that Mr. Begbie has reprinted Dr. Horton’s sermon. For this sermon, so far as it dealt with “The Angels of Mons,” was based—Dr. Horton has told me—on the supposed testimony of Miss Marrable, “the daughter of a well-known canon.” And Miss Marrable has told the world, through The Evening News, that she knows nothing at all about any angelic intervention during the retreat from Mons. I think that it would have been better if Mr. Begbie had made this clear.

Previous: Great Demand for “The Bowmen”

Next: Absolutely My Last Word on the Subject

I understand Mr. Rod Dreher is publishing a book about wonder that will relate various anecdotes. I hope that he employed something like “police court methods” in dealing with them. Firsthand testimonies often deserve attention, particularly from people (such as fiction’s Lucy Pevensie) who are habitually honest. But one can be wooed by the woo, as Machen observed (not in those words).

LikeLike

Thanks, Dale. I believe Dreher’s book is available to purchase.

LikeLike

Wow – thank you for this! Quietly swingeing on Machen’s part!

Machen notes that Begbie refers to the “furnace of Mons” – now I wonder if he picked this up from Machen, or if such terms were commonplace, and, if the latter, does this say something about general Scriptural awareness, e.g., of the King James/Authorized Version “Apocrypha” translation of the Wisdom of Solomon 3:6 – “As gold in the furnace hath he tried them, and received them as a burnt offering”? Or the same “Apocrypha” translation of the bit left out at the end of the Book of Common Prayer “Benedicite” (as verse 66): “O Ananias, Azarias, and Misael, bless ye the Lord: praise and exalt him above all for ever: for he hath delivered us from hell, and saved us from the hand of death, and delivered us out of the midst of the furnace and burning flame: even out of the midst of the fire hath he delivered us”?

Intriguing to read not only of The Daily Mail interview of a Lance-Corporal, but Begbie’s apparent follow-up: “on page 36, Mr. Begbie is examining the lance-corporal of The Daily Mail interview”! Do we know if there was more – and (from the sound of it) more reliable – investigation of his experience?

LikeLike

I am not for sure how well or deeply the Lance-Corporal’s story was investigated. Currently, I do not have access to The Daily Mail piece. However, I do have the version reported in the Evening News (9/14/1915). He remains unnamed. Yet, despite this, Machen expressed a softened tone in regards to his testimony (though it was not substantiated). He later discussed it in the the greatly expanded “Introduction” to the 2nd edition of the The Bowmen book.

In the coming months, I plan on posting the counter-narratives to Machen (as printed in the newspaper) in a followup to “Selling the Angels.” This will not only include the L-C, but Dr. Horton, Phyllis Campbell and “an unnamed nurse.”

LikeLike

Many thanks! I look forward to all this! I have been – and probably still am – insufficiently aware of the different editions of The Bowman book. In the Internet Archive, I see (A) scans of copies of the Putnam edition at Harvard and in The Library of Congress (which has what I take to be an accession stamp “OCT -7 1915”), but have not attempted any collation, (B) a scan of a copy of the Simpkin, Marshall edition in the Robarts Library of the University of Toronto, (C) two different uploads of apparently the same copy of the Caerleon edition with one saying in the description that it is in the Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad. The US Project Gutenberg transcription (“Most recently updated: December 18, 2020”) lacks bibliographical details, but seems to be from a Simpkin, Marshall copy as, e.g., it has their spelling of “organised”. Neither the Australian Gutenberg nor fadedpage has any version. So, I do not clearly see any second edition and so have no idea of “the greatly expanded ‘Introduction'” there (alas). The Caerleon has no introduction, but – I belatedly see – has a story added I have never read, “The Men from Troy”!

LikeLike

A rough bibliographical Sketch:

1st British edition by Simpkin et al.: August 10, 1915 (50K copies exhausted by early November)

2nd British edition: released before the end of 1915 in two forms (a leather cover and one in cards); extended Introduction and two extra stories. This is quite rare and I’ve never found it transcribed and posted online.

American edition by Putnam: released before the end of 1915 (same as the 1st British edition, but I’d like to check spellings between the two).

LikeLike

Thank you! I’ve just read “The Men from Troy” – and gone to the Internet Archive scan of the 1973 edition of Goldstone’s Bibliography to see when it was first published – “in The Evening News September 10, 1915, p. 2″, he says – and he also notes that it was one of the two extra stories in the Second Edition! So the Caerleon edition keeps that feature but scraps the extended Introduction (if the Digital Library of India scan is to be relied on: the pagination is clear and continuous at any rate, with no room for an Introduction).

It is quite a different story from all the explicitly Christian ones (and also from “What the Prebendary Saw” / “The Little Nations”), though it features a learned and literature-loving chaplain. And I think it would probably need a note like that included in our splendid 1992 Alfred Knopf “Everyman’s Library Children’s Classics” edition of Kipling’s Just So Stories: “Stories in this work contain racial references and language which the modern reader may find offensive. These references and language are part of the time period and environment written about, and do not reflect the attitudes of the publisher of the present edition.”

LikeLike

Just getting round to a bit of ‘homework’:

What the chaplain is reading the wounded soldier invalided home is Kipling’s short story, “The Drums of Fore and Aft”, which the Kipling Society website tells me was “First published as No. 6 in the Indian Railway Library as Wee Willie Winkie and Other Child Stories in 1889 and collected in Wee Willie Winkie and Other Stories in 1895″ and “frequently reprinted between 1895 and 1950”. It is one I have not read, but now I hope to, sometime soon. They have a transcription of the text on their site, notably prefaced “The Kipling Society presents here Kipling’s work as he wrote it, but wishes to alert readers that the text below contains some derogatory and/or offensive language” and having at the bottom of every page (e.g., also the separate linked “Background” and “Notes on the text” pages) “Some of Kipling’s works contain words or express views relating to race, gender or other matters which today are generally considered unacceptable. We are alerting readers to their presence.”

The story begins “In the Army List they still stand as ‘The Fore and Fit Princess Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen-Anspach’s Merther-Tydfilshire Own Royal Loyal Light Infantry, Regimental District 329A,’ but the Army through all its barracks and canteens knows them now as the ‘Fore and Aft.'” Knowing nothing more yet, that seems to me a fun name in the background of a Machen Great War story, with its combination of German and Welsh elements.

A thought – perhaps wildly silly – which springs to mind in the context of the wounded soldier’s discussion of the British Army as “a wonderful body of men altogether” in its range and variety – reinforced by both Kipling’s Regimental name and the details of his story Machen refers to – is that Tolkien’s “Fellowship of the Ring” drawing together such many and varied ‘peoples’ may be indebted to personal and popular perception similar to the wounded soldier’s. (Maybe that is a commonplace, I have missed – or forgotten encountering, but I am often struck by the variety of who-all served together in British, French, Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian Armies, without remembering ever making/seeing a possible ‘Middle-earth connection’.)

LikeLike

An interesting “Men from Troy” detail which I forgot to mention is the reference to the apparent rank from the wounded soldier’s perspective of his suddenly appearing ally: another sergeant for Machen’s collection!

LikeLike

I hope you will excuse my carrying on a bit, but the Homeric dimension of “The Men from Troy” got me thinking about a fascinating essay by Giuseppe Pezzini, “The Gods in (Tolkien’s) Epic: Classical Patterns of Divine Interaction”, in Tolkien and the Classical World, edited by Hamish Williams (Zurich and Jena: Walking Tree Publishers, 2021). In it, Pezzini discusses an episode in the Iliad, Book IV, which he says became “topical” and inspired “other epic writers” who re-use the “arrow-scene” – and he discusses an episode in Virgil’s Aeneid, Book XII, as an example. He summarizes: “The main features of divine interaction in classical epic are epitomised in the common imagery of the arrow” – and looks at two examples from The Lord of the Rings. In Machen’s story, the wounded soldier recalls his “pal” shouting and singing out to the “lord of the shining bow” – though no arrows are specified in what follows. But I wonder if Machen is bringing in this Homeric reference as a hint that he was playing with classical arrow imagery in “The Bowmen”.

LikeLike

Very interesting! Thank you for sharing these connections.

LikeLike

I have a memory of some scholar soldier working on an edition of a Classical author while in the trenches – I thought it was A.E. Housman, but am having no luck finding any references or details. But I did encounter recommendations of Stand in the Trench, Achilles: Classical Receptions in British Poetry of the Great War by Elizabeth Vandiver published by the OUP – and sadly 52 pounds in paperback! (But WorldCat suggests that many a library seems to have a copy…) Checking its price and availability, I find another OUP book to which she contributed with (unless I’m mistaken) different titles for the hardback and paperback editions, both of which appeared about 4 months ago: the 20-pound paperback, with chapters on Rupert Brooke, Charles Sorley, Isaac Rosenberg, and Wilfred Owen, is entitled Greek and Roman Antiquity in First World War Poetry. Under correction, Brooke, Sorely, and Owen were all officers while Rosenberg was a private. In “The Bowmen” Machen imagines a soldier with knowledge of Latin, in “The Men from Troy” a soldier with apparently no knowledge of the Classics even in translation or retelling, etc. The first seems enabled to act by his knowledge of Latin, the second to be a valuable witness by his total ignorance. There is an intriguing spectrum of play with ‘knowledge of the Classics’, here – and I wonder if Kipling is in part in the background again – as his untitled 1896 Barrack-Room Ballads poem springs to mind, with the first line “When ‘Omer smote ‘is bloomin’ lyre”.

LikeLike

Again, thanks for pointing this out. There does seem to be a stream of tradition here. Perhaps there was an intention of connecting the then-current British struggle with classic heroism from the past.

LikeLike

It suddenly springs to mind to wonder if there is any level of play in this direction in “The Men from Troy” with the the song “The British Grenadiers”. We are not (as far I can see) told anything about the wounded soldier’s regiment, but it is worth having a look at the long history and Classical references in various versions of the song in the current Wikipedia article – and in Robert Henderson’s article in the External links about the history of the text. Interesting, too, is the Imperial/Commonwealth dimension – the Canadian and Australian uses could well predate the Great War, and perhaps the list is not exhaustive. Among possible elements of play is, in this case, the Hellenes stepping in and repelling (to say the least!) this particular attack before the British troops can get involved any further after “It looked ugly for a minute or two.”

(Following the Hymnary link in footnote 9, it looks like the tune being “frequently set to different texts, including church hymns” occurred within Machen’s lifetime, but not before the Great War: “The use of this tune in a sacred context appears to have originated with the Northern (now American) Baptists and the Disciples of Christ, whose jointly published hymnal Christian Worship (1941) set it as the tune of ‘Hail to the Lord’s Anointed’.”)

LikeLike