Villette by Charlotte Brontë

By Dale Nelson

Darkly Bright recently reprinted Arthur Machen’s 25 March 1914 Evening News column, “The Critics and Mr. Henry James’s Style.” Only a little of Machen’s piece is about James. The column reviewed several books, of which the one that sounds the most enticing was a Maltese travelogue.

However, a remark made in passing ought to interest admirers of Machen’s sole book of literary criticism, Hieroglyphics: A Note Upon Ecstasy in Literature (1902). Therein, Machen proclaims the sense of wonder, or “withdrawal from the common life,” or adoration, or “desire of the unknown,” as the keynote of fine literature. One might draw the false conclusion that, for any novel to be worth his time, Machen required the presence of the overtly extraordinary.

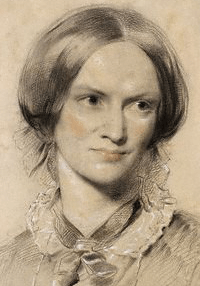

To be sure, Charlotte Brontë gave us a presentation of heightened reality in her famous Jane Eyre, of which novel Machen said it was “remarkable,” though he reserved his highest esteem for Charlotte’s sister’s Wuthering Heights (“a work of the highest genius”), where the sense of the preternatural is even stronger.

But I was happy to see Machen refer to the somber, realistic Villette as a work in which Charlotte had drawn upon the “anguish” of her soul and “transmuted” – such a Machenian verb! – that anguish by literary art.

For though Villette is not a work of heightened, intensified incident like Jane Eyre, it is nothing if it is not the story of a “soul” – to use a noun Machen was not afraid to use.

Villette was Charlotte’s last completed novel. It’s the story of Lucy Snowe, a shy, emotionally starved, and (at first) unperceptive young woman, most of whose narrative occurs during 18 months as a teacher of shallow girls in a Brussels boarding school. Though she had felt some liking for him, Lucy discourages the attentions of the school’s attractive doctor, John Bretton. She finds her soulmate instead in a short, testy instructor, Monsieur Paul Emanuel. The novel’s melodramatic element is minimal: some brief rigmarole about a ghostly nun that hardly seems integral to the novel’s meaning.

As an adult, C. S. Lewis reread the Brontë literary corpus. His friend George Sayer thought that it was perhaps Villette that was Lewis’s favorite. Lewis had first read it in his teens, praising Madame Beck and Monsieur Paul as “real, live people” in a letter to his best friend, Arthur Greeves.

There’s no reason to suppose that when the young Lewis wrote to Arthur, he had read Machen’s comment about Villette, but he could have; his letter was dated 26 Jan. 1915.

To me, the underlying outlook of Villette seemed more Gnostic than Christian, with certain spirits in the prison of this world awakening to their own innate nature – in contrast, as Lucy Snowe wrote, to the “common clay,” the “vulgar materials” that some, presumably most, people are made of. The beginning of Chapter 16 is a good statement of this “Gnostic” sensibility. (In the 20th century, the cult author Phyllis Paul wrote novels with a pronounced Gnostic sensibility.)

Why did Charlotte’s final novel evidently touch Machen? The theme of the isolated soul appealed to him, we know that. In Villette he would have found one of the world’s greatest novels to deal with this subject.

Note: Portions of this column are drawn from “Little-Known Literary Works in Lewis’s Background: A Third Selection,” in CSL: The Bulletin of the New York C. S. Lewis Society, No. 391 (Sept.-Oct. 2002)

Thank you! This intrigues, while avoiding spoilers. I know we have assorted never-yet-read Brontë-sisters’ novels on our shelves – I wonder if this is among them? I see at LibriVox that Leanne Fortune (whose L.M. Montgomery Emily of the New Moon I am enjoying at the moment) has recorded it – and that it’s 24 hours long as an audiobook (!).

LikeLike

Looking up something else, I encountered an Internet Archive scan of The Brontë Homeland; or, Misrepresentations Rectified by J. Ramsden, apparently from 1897, and note it as of possible interest.

LikeLike