The Weekly Machen

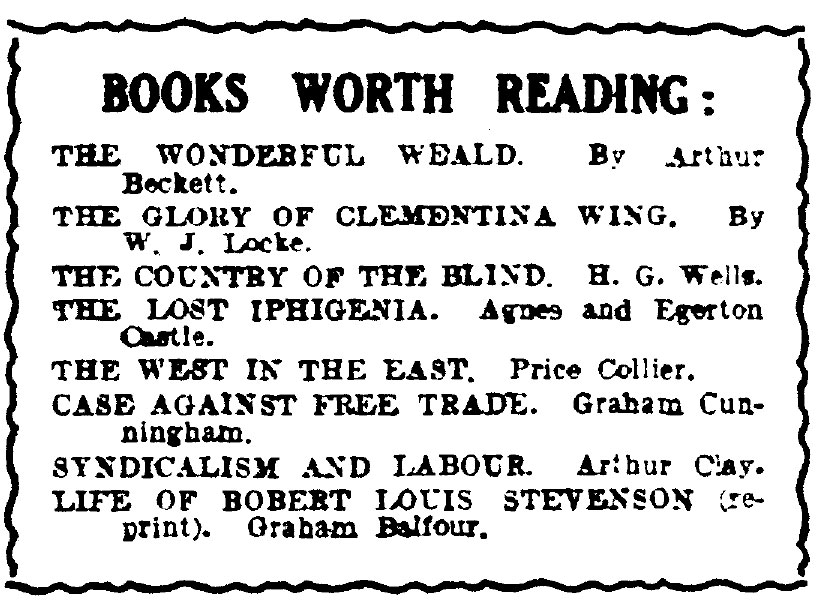

This week, we once more find Arthur Machen in the comfortable position of book reviewer. As always, his comments are insightful, humorous and rigorous. The accompanying graphic was originally placed in the middle of this column.

Books for the Autumn

by

Arthur Machen

September 5, 1911

I have a safe prediction about the coming autumn season—as safe as any of those prophecies which François Rabelais embodied in his Pantagrueline Prognostications. So, adopting an ancient method of divination, and peering into the dark crystal of the inkpot, I say boldly that the Book Season of 1911 will be very like the book season of 1910 and the book season of 1912.

Of course, there will be minor points of difference between this year and other years. For instance, I believe there is to be a new novel by Miss Marie Corelli, and I don’t think that this popular writer published anything in 1910. But I’m sure she must have issued a novel in 1909, and she may very likely oblige in 1912, and possibly in 1913 too.

There seems to me space here for a very brief note upon the work of Miss Corelli, taken generally. There are two great facts about this lady’s literary output, and, taken together, they are highly important facts. First, her work is very bad, and, secondly, it is very popular. Why is this so? Why do tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands of people take pleasure in the reading of fiction which is both crude and false? I am not going to answer the question, partly because I have not quite made up my mind on the subject, but chiefly because I am sure the real reply would run into pages—or volumes. But when we are next tempted to boast of our civilisation let us remember that a truly civilised people would not have accepted Miss Corelli as their most popular author.

A Literary Pot Pourri

To pass on: Here is a book which confirms me in my great prophecy as to the similarity that will be found to exist between the season of 1911 and other seasons. “The Romantic Past” is by Ralph Nevill, and it is published by Messrs. Chapman and Hall, and it should be called, on the analogy of “The Review of Reviews,” the “Memoir of Memoirs.” It skims over the story of Abelard and Héloise, of General Boulanger, the Taj Mahal, Villon and La Belle Heaulmière, the Fair Imperia, Henri Quatre and his fifty-six mistresses, Bonaparte, Daudet, Lady Blessington, and I don’t know how many more. It is amusing reading enough, and it may send some people to the history books and to the British Museum shelves to learn more; but where I have been able to test it—as in the account of Casanova—it is certainly not profound, nor does it give evidence of individual research. It is a microcosm of all the memoirs of gay doings that have been appearing for the last five or six years; it is as I say, a “Memoir of Memoirs.”

More serious and more profitable stuff is promised in a group of books to be issued by Messrs. Macmillan: ‘‘Tennyson and his Friends,” by Hallam Lord Tennyson, “Autobiographic Memoirs” by Mr. Frederic Harrison, and “The Record of an Adventurous Life” by Mr. H. M. Hyndman. I hope that the volume on Tennyson will give us more of the Tennyson in his slippers, as it were, and less of the public man. The latter Tennyson is best disclosed to us in the thick green volume of his poems; one would like to know more of the intimate Tennyson who liked to take his careless ease and express his careless mind in rough-and-ready sayings. He paid a visit to Caerleon, in Usk, in the ’fifties to get “local colour” for the “Idylls,” and a dignified resident of the place, calling on the poet at his inn, found him smoking a clay pipe with his feet on the chimney-piece.

Another Stevenson Edition

I shall be very interested to see what Mr. Algernon Blackwood’s “The Centaur” is like. His last book, which was called, I think, “The Human Chord,” disappointed me, because it was too technical. The Jewish Kabbalists tell us that all things will be given to him who can pronounce the Great Name of God. This, I take it, is a parable, and a very wonderful one, but Mr. Blackwood took it literally and definitely as the foundation for his story. I hope “The Centaur” will prove to be a return to his earlier method—which was admirable.

They wrote R. L. Stevenson up, and then they wrote him down; and now he taking his just place as one of the masters of English; though, as Mr. Marriott Watson once said, he is a Little Master. And in the present month, or at the beginning of October, Messrs. Chatto and Windus will begin the publication of “The Swanston Edition of the Works of Robert Louis Stevenson,” complete in twenty-five volumes, at 6s. net per volume. I am glad to see that the whole edition has been subscribed for by the booksellers. The booksellers are astute people, and we shall be pretty safe in concluding that if they have bought it, it is because they know that they can sell it. And the more Stevenson that is sold the better. Often he succeeded, now and then he failed; but he always tried. And, if I may judge from my experience of modern fiction, the author who believes in literature as a fine art, and tries to do his very best with it, is a great rarity.

The Frenchman’s Humour

M. Octave Uzanne, whose “Modern Parisienne” is to be published in a translation by the Baroness von Hutteu (Heinemann) is well-known as a master of the literary graces. I know an author who is still tickled at intervals by a review which M. Uzanne gave him more than twenty years ago. The author had written a volume of mediaeval tales, and M. Uzanne noticed it in his paper Le Livre. The review came to this: that Rabelais was asked to move a little to the right, Boccaccio a little to the left—and my friend was politely begged to take his place between his equals. He knows better, but still he liked it.

By the way, “Secret Service in South Africa” (Cassell) is a book of excellent entertainment. The authors, Mr. Douglas Blackburn and Captain Caddell, give the best picture of life in South Africa that I have ever read. There are chapters about the Transvaal Secret Service and the odd characters it employed, on the use of Witch Doctors as Intelligence Agents, on the Transvaal regarded as a sanctuary for fugitives, and on the stories of Hidden Treasure which are a perpetual mirage in South Africa, and no doubt inspired in a great measure the romances of Mr. Rider Haggard.

Previous: The Return of the Angels

Next: Story of Some Farcical Conspirators

Thanks – this is jolly! And variously tantalizing – who is the author and what is his “volume of mediaeval tales” reviewed so favorably by M. Octave Uzanne “more than twenty years ago”? And whose the commendations of the accompanying graphic? Machen’s own, having become acquainted with more review copies than he could say more about, even briefly? They seem to have different publishers (by my spottiest of spot-checks), so the answer can’t be that they’re a publisher’s advertisement…

I keep meaning to try ‘Marie Corelli’, but this does not encourage me to make haste… Her English Wikipedia article (handily linked) says both “Her works were collected by Winston Churchill, Randolph Churchill, and members of the British Royal Family, among others” and quotes François Ozon calling her “Queen Victoria’s favourite writer”! The insufficiently detailed footnote for the first assertion, a reprint of Thomas F. G. Coates and R. S. Warren Bell, Marie Corelli: The Writer and the Woman (first published in 1903: an edition found at Project Gutenberg), does, however, enable one to find (p. 147) “Queen Victoria desired that all Marie Corelli’s works should be sent to her” and quotes her publisher to her “I hope it may be that Her Most Gracious Majesty will enjoy a trip into the two worlds of her bright little subject’s creation, wherein the subject is Queen and the Queen her subject.” And says further (pp. 269-70) “From certain letters and messages Miss Marie Corelli has received from both the King and Queen (if she cared to make them public), it is very evident that she is thoroughly appreciated by the Royal Family” – but no word of Churchills, there.

LikeLike

I am not sure what volume is being referenced there. The graphic may have been a list of books that AM received, but didn’t read, or perhaps did read, but didn’t have space to include comments. Also, it may simply be a list of books received by the paper and the editors chose to honor the publishers by this abbreviated method.

I have not read Corelli, but I have read many poor opinions of her works from various literati of the period. It is interesting that she would be popular with both the populace, and as you show, Royalty.

LikeLike

Thanks for this!

I was especially struck by that Wikipedia article’s ‘Royalty’ references as I remember the Wikipedia statement in their “Mór Jókai” article that “One of his most famous admirers was Queen Victoria herself.” I have really enjoyed both his Atlantis novel and The Tower of Dago in English translation (as LibriVox audiobooks in the first instance) – and wondered what-all of his works Queen Victoria may have liked – and also what her taste in (so to say) ‘supernatural fiction’ may have been. I have not followed up the Wikipedia footnote – to Lóránt Czigány, The Oxford history of Hungarian literature from the earliest times to the present (1984) – and I assume she could not have read R. Nisbet Bain’s translation of his 1856 Atlantis novel, Oceánia, as The City of the Beast since it seems not to have been published until 1904 (though I’ve only seen the Project Gutenberg “Third Edition” of that with its Preface dated “May, 1904“). But it is fascinating, and I’ve written, but not yet published, something about it and Tolkien’s Númenor…

LikeLike

Interesting. Please inform me when the Númenor piece is published.

LikeLike