The Weekly Machen

In this installment, we find a rare instance of Arthur Machen as an elegist. While his lament is not one of verse, the following article is composed in Machen’s poetic style and incorporates some of his common themes. Machen focuses on the solemnity and awe of ritual and its importance to a spiritually and mentally healthy nation. However, the article does not indulge in a detailed account of the tragic events. No doubt, most readers were already knowledgeable of the incident, and therefore, Machen felt a recap unnecessary.

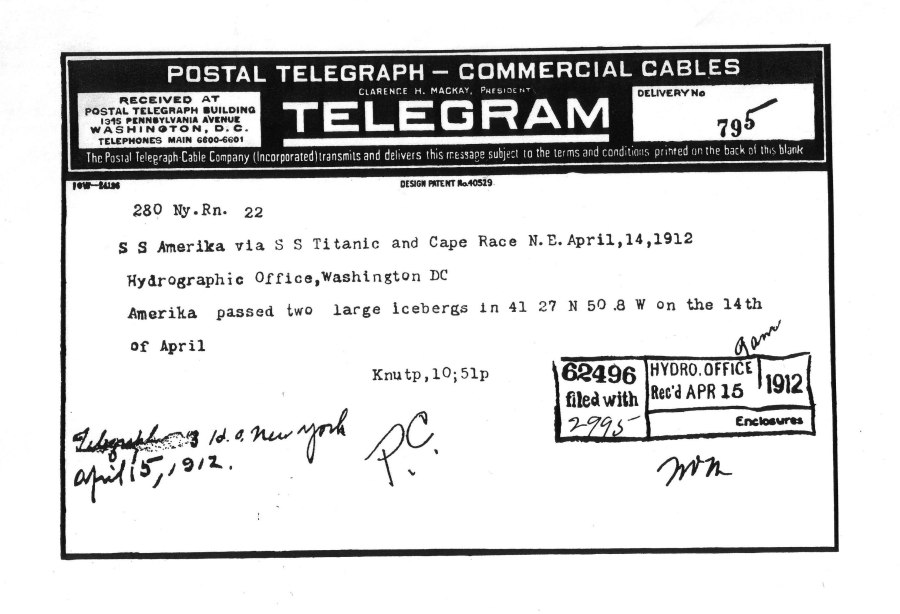

On October 4, 1912, the HMS B2, a British submarine, collided with a German ship, the SS Amerika, northeast of Dover. This resulted in the loss of the submarine and 15 crewmen. There was one survivor – a fact not covered by Machen. The Amerika survived the incident and was eventually impounded in Boston at the outbreak of World War I in August 1914. Six months before its collision with the submarine, on April 14, 1912, the Amerika sighted two icebergs during its passage across the Atlantic. Because of the weakness of that ship’s equipment, the report was relayed by the RMS Titanic (see telegram below) a day before the doomed ship struck one of those icebergs.

Following the article is appended “At the Burial of Their Dead at Sea” as found in the Book of Common Prayer 1662, which is referred to at the beginning of Machen’s story.

Into the Great Deep

by

Arthur Machen

October 11, 1912

“We therefore commit their bodies to the deep … waiting for the resurrection of the body, when the Sea shall give up her dead.”

We knew those words were being uttered, but we could not hear them across the surge and wash and swell of the waters. Even the musket fire came with a dull crackle of sound, and the notes of the Last Post seemed to shrill from far away.

This service over those drowned men of the lost submarine was surely one of the strangest that has ever been held. They, in the very act of death, were already buried: they were coffined in the boat that they had served, and as they died their roomy grave was prepared already and awaited them; even the vast and shining hollow of the sea.

It was a day of pleasant weather; one of the sweetest of these October days that are atoning somewhat for the rains and miseries of August. The sky was all blue and cloudless and the sun poured down splendours of light. But, lest this light should be too bright and hard for the solemnity of sorrow and farewell, the sea and the land faded into soft veils of mist, and the white cliffs shimmered in a vague light. (ed.- landscape as participant… {a sad landscape truly has sadness} similar to Children of the Pool)

High above the town of Dover and the sea, the castle rose in opalescent air, and the flag on the tower fluttered half-mast high.

Out of the Harbour

It was a little before one when we set out to attend the ceremony on the water. There had been a strong wind the night before, they told me, and as we passed without the harbour we met the swell running dead against us, and the little motor-boat rolled and tossed as if it had been a heavy sea. We tumbled from side to side and pitched up and down for about an hour before there was any sign of the mourners who were to be present. Dover and the castle and the cliffs were quite out of sight; here and there a ship hove up huge out of the haze: a Channel steamer, a Spanish boat, a brig from Norway. They were far off, or looked it, and appeared ghostly and phantasmal in the luminous mist.

Then quite suddenly appeared the verger and warden of the ritual of the dead. From the dimness into clear sunshine came a strange and deadly form: “black as a funeral scarf from stern to stern.” This was the destroyer Arab, and it patrolled the waters all about that place where a buoy heaved and tossed in the swell. Beneath this spot, in twenty fathoms of water, lie the drowned submarine and the drowned crew; here was the heaving graveyard to which the mourners must come in their dark procession. About and about went the destroyer, marshalling the mere sightseers to their places; flying the signal, “You are standing in to danger.”

It was two o’clock, the time appointed, and still there was no sign. But at ten minutes past two certain dark forms were seen sailing from the westward.

The fleet of the funeral advanced in four lines, headed by the three cruisers, Adamant, Forth and Minerva, and by a torpedo gunboat. Behind them were odd shapes showing above the waves: these were the conning-towers of the submarines, and after these was an array of gloomy destroyers.

The Last Rites

They came swiftly out of the mist and grew large and dark, and swiftly they took up their sad order about the buoy that swung above the hidden bodies of the dead.

There was a great silence. The sunlight was flashing on the waves; and the white paint of two or three watching steamers gleamed across the water. Very faintly one could see the cloud-like outline of the cliffs.

There was silence, save for the wash of the sea and the breaking of the waves. Every ship was dense with sailors standing in their ranks; and on the canvas-screened conning-towers of the submarines the crews stood in their working clothes, stained with the marks of the dark life they lead beneath the waters. But against all the brightness of the sunlight, and the blue sky and the glittering waves, the black order of the destroyers stood out in a deadly and dismal company. Black hulls, black funnels, black tarpaulins on their black boats; here was the meetest funeral company that ever stood about a grave.

We could not hear the voice of the priest prophesying of that final unsealing of the doors of the deep when the children of the waters should be restored by the waters that had engulfed them. The silence was broken when all had been said; the volley of the rifles came with a dull crackle, and then, as from far away, the bugle sounded the Last Post.

The Men Who Faced Death

From far away, and yet clear and entreating, rang out that last proclamation over the bodies of those who lay deep beneath the green wave and the white foam; their work accomplished, their duty done, and their last watch ended. To these dead men, shipmates of death, this was a fit farewell.

The half-mast flags flew up to the masthead and the fleet dispersed with fluttering coloured signals, some east, some west, and a long, dark line returned to their former anchorage in Dover Harbour.

To me the sorrow of such a ritual is not without comfort and better hope. I do not refer to the eternal hope of which the service of the dead is full; I mean rather that while we crown and anoint our kings in the Abbey, and offer such a ceremony as I witnessed yesterday over the bodies of brave men who constantly faced death and at last met death in a moment of time, there is still some health in us: we have not utterly surrendered ourselves to that power which is sometimes called Rationalism and sometimes Common Sense, and was fabled by an older school of theologians to possess horns and a tail.

The Apostles of Common-sense

The followers of this dubious deity would tell us that it can’t do any good to a King or to his subjects to put grease on his head and on his breast; they would be equally agreed, I am sure, that neither the dead sailors of B2 or anybody else could receive the slightest benefit from yesterday’s rites and ceremonies, which, from the rationalistic or common-sense point of view, were evidently a waste or steam-power, gunpowder, the chaplain’s voice, and the bugler’s breath.

But, so far, these “common sense” people are not altogether victorious; which on the whole is well. For when their kingdom comes, if ever it does come, the world will have the inconvenience of being neither fit to live in or to die in.

And, very certainly, it will be a world in which you will not be able to enlist submarine men to be shipmates of death and to risk their lives continuously for such unrationalistic entities as king and country.

SS Amerika

At the Burial of Their Dead at Sea

We therefore commit his body to the deep, to be turned into corruption, looking for the resurrection of the body, (when the Sea shall give up her dead,) and the life of the world to come, through our Lord Jesus Christ; who at his coming shall change our vile body, that it may be like his glorious body, according to the mighty working, whereby he is able to subdue all things to himself.

Previous: The War Behind War

Next:

A descriptive and thoughtful piece from Machen.

The idea of being anointed is important in the conclusion of Machen’s novella “The Terror.”

https://wormwoodiana.blogspot.com/2019/12/guest-post-balm-of-consecration-in.html

Here he shies away from a theological justification of the solemn ceremony he describes, and chooses to commend it on conservative social grounds that make sense as far as they go. He reminds me of C. S. Lewis on the monarchy in his essay “Equality,” particularly its penultimate paragraph. (It may be found in the book Present Concerns.)

LikeLike

I just tried to add a comment to Dale Nelson’s linked post, but do not see that I succeeded, so I will venture to add it, here.

I wonder if Charles Williams may have know “The Terror” as well as “The Great God Pan”, and if there may be any conscious connection with it in his novel, The Place of the Lion. There is also a dimension in his Arthurian poetry of Arthur as King representing Man with the knights with their heraldic animals being properly subordinated to him as faculties and capacities of Man, with Arthur then re-enacting, or peculiarly participating in the Fall of Man and pitching the knights and kingdom into spiritual disorder too.

Following on from Machen’s article about his visit to the Orthodox Church in London, I wonder how aware he was of chrismation as part of the service of Confirmatio among them.

It is probably worth mentioning that when Machen says “there is still some health in us” he is recalling in a striking fashion the general Confession at Morning and Evening Prayer in which the whole congregation say “after” or with “the Minister, all kneeling”, “there is no health in us”! For the first confession of sin is there followed by prayers for mercy, restoration, and that God grant “That we may hereafter live a godly, righteous, and sober life, To the glory of thy holy Name.” If ‘we’ mean it when we pray in Coronation, Burial, and Confession there is some ” health in us” and the hope of more.

LikeLike

David, it’s a regrettable thing that, while we know Charles Williams read a lot, we don’t seem to know much about his reading (other than books he reviewed, many of them mystery fiction, or referred to (e.g. as in footnotes in The Descent of the Dove). There may be many places in Williams’s sometimes partially opaque writing in which he was thinking of something he had read, such that his meaning would be clearer if we knew what that book or poem or article was. I think some Williams readers might make too much of Williams’s reading in “occult” material relative to these unknown works, whether scholarly or otherwise. And his reading of Machen is something I’d put high on a list of things I wish I knew more about.

LikeLike

I wish we had reviews by Machen of The Passion of Christ (1939) and The New Christian Year (1941) – I can imagine that he would both be delighted and have interesting things to say, even, uniquely interesting. What astonishing books they are – especially the latter – how wide and varied the reading behind them, and how interesting the selections and the juxtapositions, with the days of the (Book of Common Prayer) year and between quotations. Happily anyone online can read them as intended, thanks to:

https://tomwills.typepad.com/thenewchristianyear/

and now easily purchase a paper copy, too, if preferred.

LikeLike