Introduction

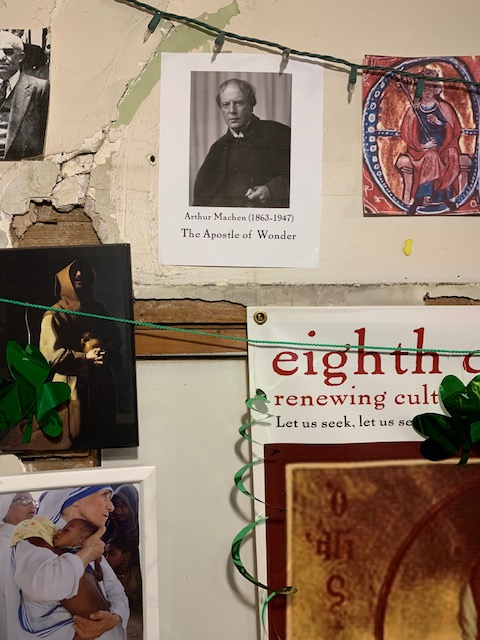

On March 10, 2022, poet and essayist Joshua Alan Sturgill presented a lecture on Arthur Machen to the Hall of Men, a monthly program of the Eighth Day Institute for like-minded fellows to meet and toast their heroes. This night completed a year-long series of events in which Machen was explored and honored, beginning with a discussion of Levavi Oculos at the 2021 St. Patrick’s Celebration, and most prominently, the Apostle of Wonder took center stage at the Inklings Festival last October. As Fr. Geoffrey Boyle, president of EDI, expressed it: “We need to add Arthur Machen to our repertoire of Inklings and Francis Thompson to our wall of heroes.”

The Wall of Heroes at The Ladder in Wichita, Kansas

In Praise of Arthur Machen

by

Joshua Alan Sturgill

Arthur Machen—1863-1947—Welsh, and a “Cambrophile,” a lover of and historian of Wales. Descendant of a long line of clergymen. Of course, there are many biographical details I could give you, but I won’t.

Instead, I want to leave you with two impressions:

First, Machen’s long though hidden influence on modern writers, including Stephen King (who called The Great God Pan the greatest horror story in the english language) and Charles Williams (whose “spiritual novel” style was directly reflective of Machen’s work).

Second, most importantly, of what I believe is the main philosophical reason behind Machen’s work as a literary artist—his vision and motivation.

Around 1900, Machen’s wife died of cancer, and this in part led to his briefly joining The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an occult society dedicated to promoting paranormal studies and experiences. This is unsurprising. It seems that many eminent Victorians dabbled in the occult. It was the “extreme sports” of its day.

His official association with the Golden Dawn was short-lived, but it left a lasting impact on Machen’s worldview. Namely: personal tragedy and the shallowness of occult answers made him more aware of the eternal value of life and of the unplumbed depths of Christian faith.

It’s important to know Machen was living in a time when the Industrial Revolution had completely taken over society, not only materially, but psychologically as well. The physical sciences had subtly become a philosophy of scientism, and simultaneously, the Christian faith (which had already been reduced to a philosophy for some centuries) induced sentimentalism at best and skepticism at worst in the educated classes.

The Victorian Age was a time when intellectuals were seeking something other, something MORE from life. Faith and science had airtight systems for delineating and then explaining everything within their bounds. But many people strongly sensed that religious and scientistic explanations couldn’t account for the full breadth of Reality.

In this of course, Machen’s experience is not much different than our own. We still live in a world of Fundamentalisms, a world of reductions and syllogisms. We live both in the world of Four Spiritual Laws/Print-on-demand shallow spirituality and in the world of Four Fundamental Laws/Follow the Science shallow cosmology.

Whatever truth or goodness might be in these ideas has completely overshadowed Christ’s admonitions to “endure to the end” because He alone is the “Light of the World”—in other words: religion should be about our ever-increasing knowledge of the unknowable God, and physics should be about all things that have come into being through Him.

Machen was not content with easy-believism in either science or religion. He wanted to shake people out of their sleep. He wanted Christians who were not just aware of their faith, but who were the actual face and hands of God in their generation. His task: to use his talent as a writer to shock us into consciousness.

He did this shocking both through essays and through “horror fiction.” Horror will require a little explanation. With its relatives horrid, horrible and horrifying, the word comes from a Latin root meaning to “shudder” or “tremble deeply.”

Machen’s work is meant to cause shuddering at what is always present around us, but rarely seen. His fiction work is suggestive and descriptive, rather than exciting and gory, and his essays always gravitate toward the transcendent in everyday things.

Machen was an enthusiast for all literature that dealt with rapture, beauty, adoration, mystery, a sense of and desire for the unknown. He summed up these attributes in the word ecstasy. In fact, Machen believed that Adam and Eve were created for ecstasy. They were created precisely to be intoxicated with God.

A few years ago, one of our writing groups connected with EDI considered some of T.S. Elliot’s thoughts on the importance of local writers. What he meant is that there are many famous, broad-appeal writers in the world, but very few of them teach us practical Beauty and communal Truth.

Machen seems to be the kind of writer who knows what project he’s working on and doesn’t care whether his work gains him any kind of popularity. He is essentially a local writer in Elliot’s sense, especially in his works describing the reemergence of the evil or the holy in villages, houses, and personal choices, as in his The Great Return.

I would say that, anchored in the local, Machen has a universal project. I often tell my poetry students to remember the axiom “specific is cosmic,” meaning that the great ideas are best expressed not in abstract generalities but in concrete details.

If I could give a title to Machen’s project, I would use his own words and call it a struggle towards Unveiling the Secret Language.

Machen believed that the world as a whole and the things in it—from coins and chairs to clouds and stars—are God’s grammar and syntax. These substantial words are always spoken and always heard, but rarely listened to. Machen wanted the people around him to heed the call echoed in the Orthodox Liturgy: “Here is Wisdom! Let Us Attend!”

Here are a few passages adapted from Machen’s essay on the Secret Language. It’s worth reading in full—especially if you’re interested in what it means to be a good writer.

Now remember: the two impressions I want to give you are

1. Machen as an influential writer. And

2. Machen as a man with a deliberate message in mind about the nature of the world.

These (slightly paraphrased) quotes will help clarify his message more exactly:

Things which are most clear may be most hidden, and hidden for long ages, and hidden not only from the gross and sensual man, but from fine and cultured men. That being evident, does not the consequence follow that we, too, gaze at great wonders both of the body and spirit without discerning its marvels all around us?

It would appear that we may be groping after the perception of things which we apprehend [only] in a dim and broken and imperfect manner.

Let me say it here: in the Christian Faith, the highest and final and uttermost mystery is contained in the simplest rite in the world, in the matter of natural, familiar, physical things which all men know and taste and see—that is, in bread and in wine.

The manner in which the Christian religion protests against all the horrible heresies which, under various disguises, have taught that the world and all therein is the work not of a God but of a devil is that it signifies spiritual things by the gate of sensible things. This is the secret language, open to all but disregarded by all…

This secret language of the visible universe, though it may not be openly spoken, is everywhere whispered.

Finally, I’ll leave you with Machen’s definition of true literature, which is the Secret Language well expressed.

To understand this last selection, you should know that Machen was delivering this lecture on the Secret Language to a group of Theosophists (another occult society concerned with Eastern texts and mysticism). Machen is no longer in the occult at this time. He’s a high-church Anglican, though he refers here to a passage found in Orthodox, but not often in Western bibles, where the children in the fiery furnace call on all of Nature to praise God with them.

I refer you often to the Holy Scriptures. I know it is an Eastern book, but it has been long translated into the tongues of the West…. Still the Psalm Benedicite omnia opera*—to put a good Latin face on it—is much to my purpose: I would ask you to think over these measured appeals to rains and dew, winds and fire, winter and summer, frost and cold, ice and snow—that these things should “bless the Lord, praise and magnify Him forever”—all of these are the commonest of common things, yet they are addressed by the Holy Youths as fellow creatures in the Eternal Chorus. They are so addressed, I believe, because they, too, according to their degree, utter the Eternal Word, and though they are of earth, they speak to the wise ever of unearthly wonders.

Thus, I think it is that if you know how to describe a lonely man stumbling on his way up a long, winding lane on a winter’s night, buffeted with mountain winds, drenched with driving rains, overwhelmed with darkness—and yet attaining at length to a homely shelter, to a seat by a roaring fire, to a place whence he can listen to the storm outside … well, incidentally, you have made literature.

But essentially, you have described the passage into Paradise.

Note

* Benedicite, omnia opera is a canticle authorized for use during Morning Prayer in the Book of Common Prayer, 1662. This is also known as the Hymn of the Three Young Men found in the third chapter of the Book of Daniel. In many Western versions of the Bible, it is appears separately as an apocryphal book.

In Praise of Arthur Machen: Copyright 2022 by Joshua Alan Sturgill. All rights reserved.