Dreamt in Fire: The Dreadful Ecstasy of Arthur Machen

by

Christopher Tompkins

The following is an edited version of a lecture given at 2021 Inklings Festival held by the Eighth Day Institute in Wichita, Kansas.

“…thus I think it is that if you know how to describe a lonely man stumbling on his way up a long and winding lane on a winter’s night, buffeted with mountain winds, drenched with driving rains, overwhelmed with darkness, and yet attaining at length to homely shelter, to a seat on the settle by a roaring fire, to a place whence he can listen to the storm without; well, incidentally you have made literature, but essentially you have described the passage into Paradise. And that, by the way, is no doubt the true definition of literature—of the secret language well-expressed; it must deal with the passage to Paradise.”

Since first reading that quote, it has stuck with me as if I had found a solitary lamppost burning on an uncharted wasteland. Here is a second quote like unto it, but shorter:

“And so I go on and say that you cannot write of anything, or make the image of anything, without writing of God or making the image of veiled divinity.”

I find this set of quotes extraordinary, not only because the content is ineffably true, but that such emerges from the pen of a little-known figure most often pigeonholed as a writer of horror fiction. Now this creates a juxtaposition for us which may lead us to consider that there must be something more to such a writer, and perhaps, more to the horror genre as a method of describing the human condition.

On that last point… stay tuned for tomorrow’s episode… if you dare.

You may be curious as to how I stumbled across such an obscure figure. Well, I’ll tell you anyway. I’m a guy who digs old, smelly books. And, coupled with an insatiable desire to wander down strange foot paths, I am obsessive in my attention to what could be termed the marginalia of literature… the sad sort who prefers the appendices to the main text of The Lord of the Rings. I always feel like I must apologize for that… to normal people.

These habits and character defects are precisely how I found Arthur Machen, but the details of that discovery is perhaps out of scope for this talk and certainly not allowable due to time. In fact, after spending so many years studying Machen, I feel that I have enough material to conduct a week of nightly lectures, but for your sake, I’ve been limited to a single hour in which to torture you, so we must make the best of it. And yet, there is so much I could speak about: of course his most read stories of wonder and fear, the wildness of his modern fairy tales, the mass of his Christian apologetics, his studies on religion, liturgy and literature, the restless war years which gave him a brief brush with fame and his original scholarship on Celtic hagiography and the Grail legends. On that last topic, we’re fortunate to have Richard Rohlin and no doubt he will offer some wonderful insight. But tonight, we have yours truly, and as I say, we must make the best of it.

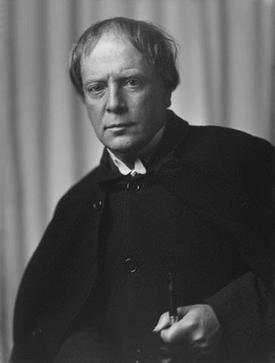

Who then is Arthur Machen? Arthur Llewellyn Jones-Machen was born in 1863, the son and grandson of Anglican priests. He was an only child of a poor clergyman in South Wales, but enjoyed his childhood, an existence that could have proved unbearably lonely had it not been for his introspective temperament. He often spent his days walking miles in the countryside while spending his nights enraptured by The Arabian Nights and Don Quixote. Unable to pay for University, Machen was sent as a young man to London which produced as much wonderment as had his rural homeland.

Who then is Arthur Machen? Arthur Llewellyn Jones-Machen was born in 1863, the son and grandson of Anglican priests. He was an only child of a poor clergyman in South Wales, but enjoyed his childhood, an existence that could have proved unbearably lonely had it not been for his introspective temperament. He often spent his days walking miles in the countryside while spending his nights enraptured by The Arabian Nights and Don Quixote. Unable to pay for University, Machen was sent as a young man to London which produced as much wonderment as had his rural homeland.

After failing to find a stable profession, Machen took the reasonable course… he set out to be a writer and self-published his first book, a pamphlet entitled Eleusinia which featured one long poem. This edition of 100 copies is rare with only 1 specimen known to have survived. However, he wisely gave up poetry, for in truth he was a poor architect of verse, even though his subsequent prose would prove to be exceedingly poetic. Dreadfully poor, Machen at first found life in London difficult, but never lost his relish for its streets and and neighborhoods. After stints at various jobs including tutoring, he began work as a cataloguer and translator. In the 1880s, his 12 volume translation of the Memoirs of Casanova, the first in English, was published and remained the premier version being regularly reprinted and read until the 1960s.

After marrying, Machen published several stories in the 1890s which proved quite shocking to the Victorian reading public, though it is bit challenging for some modern readers to understand why. In 1899, Machen’s wife died of cancer and this sent him into a mental and spiritual crisis. He played a brief stint in the occult scene of the era, but Machen grew quickly bored of the hocus-pocus, as he later described it. Surprisingly, he became an actor on the stage by joining a touring company in 1901. Though relishing the life of an actor, Machen married a second time, so therefore, he required a more stable career.

He began writing essays and reviews for The Academy journal, a literary periodical then owned by Lord Alfred Douglas, the former lover of Oscar Wilde. Later, Douglas would credit Machen with pointing him toward Christianity. While at the journal, Machen, a High Church Anglo-Catholic, wrote in defense of Catholicity within the English Church. In this regard, he shared some similarities with early Chesterton, but he never converted to Rome as the latter did.

During this time, Machen published two books of great importance to his bibliography. Firstly, came House of Souls, which would become the classic collection of his work from the 1890s. Secondly, he released a novel, Hill of Dreams, considered by some to be his greatest book. The story presents the spiritual odyssey of a young man drawn to literature.

By necessity, Machen spent the second decade of the twentieth century in a profession he would abhor: journalism. He did so to support his young family, but it came at a high cost. Ironically, it was his tenure at the Evening News that provided him with his greatest fame. In 1914, the British Expeditionary Force barely survived the onslaught of the superior German army at the Belgian city of Mons. Inspired by the near miraculous development, Machen penned a short, and admittedly weak tale entitled The Bowmen which described St George, the patron saint of England and a spiritual army of archers coming to the aid of the British. It was published, but to Machen’s surprise it was taken as fact and morphed into the Angel of Mons legend, a strange concoction of spirituality and propaganda. The truth and fancy of this incident are too deeply woven to attempt a full explanation, but quite simply, Machen, who felt the truth was more important than comfortable fantasy, was outnumbered and fought a losing battle in the press. In fact recent research suggests that British intelligence may have encouraged public opposition to the author: Machen contra mundum.

By necessity, Machen spent the second decade of the twentieth century in a profession he would abhor: journalism. He did so to support his young family, but it came at a high cost. Ironically, it was his tenure at the Evening News that provided him with his greatest fame. In 1914, the British Expeditionary Force barely survived the onslaught of the superior German army at the Belgian city of Mons. Inspired by the near miraculous development, Machen penned a short, and admittedly weak tale entitled The Bowmen which described St George, the patron saint of England and a spiritual army of archers coming to the aid of the British. It was published, but to Machen’s surprise it was taken as fact and morphed into the Angel of Mons legend, a strange concoction of spirituality and propaganda. The truth and fancy of this incident are too deeply woven to attempt a full explanation, but quite simply, Machen, who felt the truth was more important than comfortable fantasy, was outnumbered and fought a losing battle in the press. In fact recent research suggests that British intelligence may have encouraged public opposition to the author: Machen contra mundum.

However, the publicity did allow him to publish more accomplished war stories including The Great Return and The Terror. Additionally, he published a volume of apologetics entitled War and the Christian Faith, though not as famous as Lewis’s later war-time work, this book was written under similar circumstances and addressed many of the same themes.

However, the publicity did allow him to publish more accomplished war stories including The Great Return and The Terror. Additionally, he published a volume of apologetics entitled War and the Christian Faith, though not as famous as Lewis’s later war-time work, this book was written under similar circumstances and addressed many of the same themes.

By the 1920s, Machen had left journalism, yet continued to scratch out a meagre existence. He was never wealthy, but by this time, he had found peace with his lot. Relief came from an unlikely source: America. Slowly, appreciation for this obscure writer had been developing among critics and book collectors. A prophet is not honored in his own country, I suppose. This Machen Boom of the Twenties, as it was called, created a new opportunity for the aging British author. Old books were reprinted on both sides of the Atlantic and the demand for new works began. In 1922, Machen published The Secret Glory, a novel he had completed roughly 14 years before. A series of short prose pieces, written in 1890s, were finally collected in Ornaments in Jade, one of his most beautifully crafted books. Three volumes of memoirs hit the shelves as well as several collections of his best essays.

One book I’d like to elaborate on is Precious Balms, a collection of critical reviews of his work that Machen had collected over the years. Though he includes some positive pieces, he preferred to highlight the negative notices. In the introduction he defines the art of the bad review and notes that he never understood why writers feared them. “Opposition is the relish life,” he claimed. In his memoirs, there is a recurring motif of resilience which reflects this belief. Many times after receiving a bad notice, Machen smiled and with joy began another book. When once asked about his current project, Machen responded: “I am writing a book that everyone will hate.” I can’t help imagining a gleam in his eye when said it. That book turned out to be The Secret Glory.

In the 1930s, Machen produced a final burst of new work by publishing a novel and a collection of excellent stories, The Children of the Pool, in which he revisits his classic themes. His final story was published in 1937. In 1943, Machen was treated to a grand dinner in honor of his 80th birthday and was awarded a monetary gift raised by publishers and authors such as George Bernard Shaw and T. S. Eliot. This allowed his final years to be comfortable ones. The Apostle of Wonder, as one biographer anointed him, died at the age of 84, a second-time widower.

I went through that material rather quickly, but essentially, that is the relevant data of his life. Now, I’d like to shift our focus to the substance of Arthur Machen’s work.

In 1902, Machen published a book of criticism entitled Hieroglyphics, a manifesto of his literary theory. In determining the difference between books as “reading matter” and books which constitute the high art of literature, Machen asks to us lay aside commonly held arguments such as “It made me feel,” “I couldn’t put the book down,” or even “I liked it.” Of course, such claims intend to prove that a particular work is “literature,” but Machen will have none of it. It is not enough that a story conveys a cleverly devised plot, “realistically” rendered characters or a sense of fidelity to so-called real life.

In 1902, Machen published a book of criticism entitled Hieroglyphics, a manifesto of his literary theory. In determining the difference between books as “reading matter” and books which constitute the high art of literature, Machen asks to us lay aside commonly held arguments such as “It made me feel,” “I couldn’t put the book down,” or even “I liked it.” Of course, such claims intend to prove that a particular work is “literature,” but Machen will have none of it. It is not enough that a story conveys a cleverly devised plot, “realistically” rendered characters or a sense of fidelity to so-called real life.

He asks to recall Thackeray. Machen admits a personal admiration for Vanity Fair; he enjoys the exploits of Becky Sharp, yet the book fails to meet his criteria. Thackeray, he observed is a photographer, a clever photographer, a showman, but he sees and records only the surface of things. He writes of the accidents of literature not its essentials. Through setting, dialogue and other accidents, Thackeray invents. But, invention is not creation.

Man is a sacrament, Machen argued, a mystery. While books such as Vanity Fair are entertaining and have their place, he asks us to look higher, deeper when we consider which stories constitute literature. What is Machen’s solution? I’ll quote him:

“…for me the answer comes with the one word, Ecstasy. If ecstasy be present, then I say there is fine literature, if it be absent, then, in spite of all the cleverness, all the talents, all the workmanship and observation and dexterity you may show me, then, I think, we have a product (possibly a very interesting one), which is not fine literature. Substitute, if you like, rapture, beauty, adoration, wonder, awe, mystery, sense of the unknown, desire for the unknown. All and each will convey what I mean.. but in every case there will be that withdrawal from the common life and the common consciousness which justifies my choice of ecstasy as the best symbol of my meaning.”

For Machen, great works of Literature are imbued with hieroglyphs, with iconic imagery that speaks to readers in a secret language. When we discover the Holy Grail while reading the legends, we instantly intuit what that symbol means without it being explained to us. We can describe this approach as a defense of universal stories… of the mythopoeic vision.

He writes: “All the profound verities which have been revealed to man have come to him under the guise of myths and symbols.” The development of these symbols is the role of the artist.

And again, he says: “We read the Odyssey because we are supernatural, because we hear in it the echoes of the eternal song, because it symbolises for us certain amazing and beautiful things, because it is music; we read Jane Austen and Thackeray because we like to recognise the faces of our friends aptly reproduced, to see the external face of humanity so deftly mimicked, because we are natural.”

Machen recognized Don Quixote and Sancho Panza as universal symbols, and divined in Huckleberry Finn, a Homeric voyage into the unknown. He considered these stories to be “true,” and therefore, he claimed Literature to be concerned with realism… to recognize that Man, and the Cosmos have interior meaning. For Machen, this theory extends to the world around us. He sees a hieroglyph in the song of a bird or in the blossoming of a flower. This set of beliefs lead him to conclude his book Hieroglyphics in this way:

“You ask me for a new test—or rather for a new expression of the one test—that separates literature from the mass of stuff which is not literature. I will give you a test that will startle you; literature is the expression, through the æsthetic medium of words, of the dogmas of the Catholic Church, and that which in any way is out of harmony with these dogmas is not literature.”

Now, let us keep all that in mind – the sacramental reality of man and nature and the catholicity of literature – and put our theorist to the test.

To begin, we should note that Machen’s work revolves around two sets of polarities. First, we find narratives which are either dark or bright, in other words, stories composed in the mode of horror and those which feature awe in the presence of holy people and things. Both of these modes are found in the second of Machen’s polarities: that of place. His stories are always situated in the great metropolis of London or in the countryside of his native Wales. Danger and wonder can be found in both locations. Therefore, landscape plays as a vital role in his work as character and action.

Before we move to his fiction, we should note the importance of landscape to Machen as it is presented in his first volume of memoirs, Far Off Things. I’ll quote a passage:

“I shall always esteem it as the greatest piece of fortune that has fallen to me, that I was born in that noble, fallen Caerleon-on-Usk, in the heart of Gwent. For the older I grow the more firmly am I convinced that anything which I may have accomplished in literature is due to the fact that when my eyes were first opened in earliest childhood they had before them the vision of an enchanted land. As soon as I saw anything I saw Twyn Barlwm, that mystic tumulus, the memorial of peoples that dwelt in that region before the Celts left the Land of Summer. One could see the pointed summit of the Holy Mountain. It would shine, I remember, a pure blue in the far sunshine; it was a mountain peak in a fairy tale. And then to eastward… away to the forest of Wentwood, to the church tower on the hill above Caerleon. And of nights, when the dusk fell and the farmer went his rounds, you might chance to see his lantern glimmering a very spark on the hillside. This was all that showed in a vague, dark world; and the only sounds were the faint distant barking of the sheepdog and the melancholy cry of the owls from the border of the brake.”

“I shall always esteem it as the greatest piece of fortune that has fallen to me, that I was born in that noble, fallen Caerleon-on-Usk, in the heart of Gwent. For the older I grow the more firmly am I convinced that anything which I may have accomplished in literature is due to the fact that when my eyes were first opened in earliest childhood they had before them the vision of an enchanted land. As soon as I saw anything I saw Twyn Barlwm, that mystic tumulus, the memorial of peoples that dwelt in that region before the Celts left the Land of Summer. One could see the pointed summit of the Holy Mountain. It would shine, I remember, a pure blue in the far sunshine; it was a mountain peak in a fairy tale. And then to eastward… away to the forest of Wentwood, to the church tower on the hill above Caerleon. And of nights, when the dusk fell and the farmer went his rounds, you might chance to see his lantern glimmering a very spark on the hillside. This was all that showed in a vague, dark world; and the only sounds were the faint distant barking of the sheepdog and the melancholy cry of the owls from the border of the brake.”

Of course it would be a mistake to assume Machen to be a pastoral sentimentalist. To illustrate Machen’s nuanced concern for landscape, I’d like to introduce you to a passage from The White People, one of the most frightening stories I’ve ever read, and which deals with the experience of a young girl, absolutely unprepared to deal with forces which confront her, and who therefore falls into utter dissolution. The following passage, Machen tells us, is found in the young girl’s diary:

“It was winter time, and there were black terrible woods hanging from the hills all round; it was like seeing a large room hung with black curtains, and the shape of the trees seemed quite different from any I had ever seen before. I was afraid. I went on into the dreadful rocks. There were hundreds and hundreds of them. Some were like horrid-grinning men; I could see their faces as if they would jump at me out of the stone, and catch hold of me, and drag me with them back into the rock, so that I should always be there. And there were other rocks that were like animals, creeping, horrible animals, putting out their tongues, and others were like words that I could not say, and others like dead people lying on the grass. I went on among them, though they frightened me, and my heart was full of wicked songs that they put into it.”

From this, we can detect not only an interest in haunted places, but another important theme, for many of Machen’s early stories serve as meditations on the nature of evil. In the prologue to The White People, Ambrose, a Christian in possession of that girl’s diary, speaks Machen’s meaning:

“‘Sorcery and sanctity,’ said Ambrose, ‘these are the only realities. Each is an ecstasy, a withdrawal from the common life. The saint endeavours to recover a gift which he has lost; the sinner tries to obtain something which was never his. In brief, he repeats the Fall.’”

Yet, to our relief, Machen is not content to consign us always to that horrid field of stones. He will not leave us in despair. In what could be described as a delayed Eucatastrophe, he will provide an antidote as we will see shortly.

If landscape provides a complex backdrop which is colored by narrative mode and setting, how do specific hieroglyphs act in Machen’s fiction? I will attempt to illustrate a few examples in detail. Again, these examples highlight Machen’s use of dark and light modes in both of his favored locations.

Stephen King has commented that Machen’s The Great God Pan may be the greatest short horror story in the English language. As on many other matters, I audaciously disagree with Mr. King. Rather I suggest another short story by Machen fits that description: The Inmost Light. But more that masterwork tomorrow morning. Tonight, let us examine The Great God Pan.

For a bit of background, it is quite illuminating to consider the resurgence of interest in Pan throughout Western art and literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as this ribald pagan god of nature appears in poems, paintings and musical compositions in various depictions. Fauns, satyrs and nymphs naturally rode this wave of renewed popularity. Of course, we are familiar with C. S. Lewis’s family-friendly faun Mr. Tumnus from the Narnia Chronicles. E. M. Forster treats such a figure humorously in The Curate’s Friend. Unnamed, Pan himself makes a benevolent appearance in Graham Greene’s The Wind in the Willows.

Others however took a dimmer view. Amyas Northcote’s story In the Woods depicts the physical and spiritual danger facing those who take too deeply to heart a devotion to nature in and of itself. H. D. Everett‘s The Next Heir deals darkly with a modern worship of Pan, who, quite interestingly, is identified as Cain.

This thread of Pan stories harkens back to some of the original myths in which the figure is shown to be dangerous, wild and lascivious. Plutarch commented that Pan, though a god, actually died, leading the early Christian historian Eusebius to suggest that this referred to the fall of the powers of darkness due to the victory of Jesus Christ.

So, indeed, we readily see variety in the treatment of Pan and Pan imagery. Is there any question as to where Arthur Machen would fall on this spectrum? Well, to vanquish any doubt, I offer a brief synopsis of his story.

In the wilds of Wales, a scientist, amoral in his disregard for others, performs brain surgery on a young woman allowing her to see the Great God Pan. This causes madness, and eventually death, but she does give birth to a female child. The story ellipses to years later, when an horror stalks the gaslit streets of London. A rash of suicides by prominent men fuel the sales of newspapers. Through a series of episodes, the source of this evil is found to be a “woman” named Helen Vaughn, who is literally without a soul. She spiritually and physically debauches the victims, sending them into despair. Of course, she is the daughter of Pan.

In the wilds of Wales, a scientist, amoral in his disregard for others, performs brain surgery on a young woman allowing her to see the Great God Pan. This causes madness, and eventually death, but she does give birth to a female child. The story ellipses to years later, when an horror stalks the gaslit streets of London. A rash of suicides by prominent men fuel the sales of newspapers. Through a series of episodes, the source of this evil is found to be a “woman” named Helen Vaughn, who is literally without a soul. She spiritually and physically debauches the victims, sending them into despair. Of course, she is the daughter of Pan.

In the narrative, the reader never directly encounters the eponymous being, but once unleashed by man’s unrighteous thirst for unrevealed knowledge, the effects are violent. For Machen, Pan is a hieroglyph for paganism and its unbridled sensuality, its carnal violence, its activity without morality. In the face of it, men perish. Additionally, Machen’s story is an attack on the Cult of Scientism, a body of belief statements claiming to be the sole font of knowledge in regards to the natural world, most often without a divine reference point. Machen doesn’t disregard science. In a late letter, he counsels a friend to remember that science can only tell us about the surface of things.

If we were to look at our current culture, I wonder if we could discern the worship of Pan continuing unabated in myriad forms?

For the next examples of Machen’s use of hieroglyphics, we will experience a reversal. This time, in The Great Return, we begin in London and journey to rural Wales. The Great City, weary from the First World War, is described in this way:

“Indeed, the torment of the world was in the London weather. The city wore a terrible vesture; within our hearts was dread; without we were clothed in black clouds and angry fire.”

After receiving odd bits of information, our narrator travels to the Welsh countryside, and upon arrival, he immediately illustrates the landscape with the following:

“It is certain that I cannot show in any words the utter peace of that Welsh coast to which I came; one sees, I think, in such a change a figure of the passage from the disquiets and the fears of earth to the peace of paradise. A land that seemed to be in a holy, happy dream, a sea that changed all the while from olivine to emerald, from emerald to sapphire, from sapphire to amethyst, that washed in white foam at the bases of the firm, grey rocks, and about the huge crimson bastions that hid the western bays and inlets of the waters; to this land I came, and to hollows that were purple and odorous with wild thyme, wonderful with many tiny, exquisite flowers. There was benediction in centaury, pardon in eye-bright, joy in lady’s slipper; and so the weary eyes were refreshed, looking now at the little flowers and the happy bees about them, now on the magic mirror of the deep, changing from marvel to marvel with the passing of the great white clouds, with the brightening of the sun.”

“It is certain that I cannot show in any words the utter peace of that Welsh coast to which I came; one sees, I think, in such a change a figure of the passage from the disquiets and the fears of earth to the peace of paradise. A land that seemed to be in a holy, happy dream, a sea that changed all the while from olivine to emerald, from emerald to sapphire, from sapphire to amethyst, that washed in white foam at the bases of the firm, grey rocks, and about the huge crimson bastions that hid the western bays and inlets of the waters; to this land I came, and to hollows that were purple and odorous with wild thyme, wonderful with many tiny, exquisite flowers. There was benediction in centaury, pardon in eye-bright, joy in lady’s slipper; and so the weary eyes were refreshed, looking now at the little flowers and the happy bees about them, now on the magic mirror of the deep, changing from marvel to marvel with the passing of the great white clouds, with the brightening of the sun.”

This description is of course reminiscent of the earlier quote from Machen’s memoirs. And again, recall the wretched rocks from The White People… elsewhere in The Great Return, we read that the very stones appear to be living stones. An alchemy has taken place.

And with such alchemical language, we find another carefully chosen hieroglyph, one that sings of transmutation and of transfiguration. Not only did the narrative of this story take place during the Great War, it was written and published during that conflict. Why would Machen write the previous words under such conditions of wholesale butchery waged on industrial scale? And, perhaps more to our concern, on the fictional plane: how can such a redeeming alchemy occur in light of this unprecedented terror?

The answer is a completely unbelievable one. As one contemporary reviewer expressed it, this story could be described as ludicrous. Borne by three Celtic Saints, the Holy Graal returns to the village of Llantrisant, which translates as Parish of the Three Saints, and by doing so, the Cup transfigures the landscape. Not the landscape only, but all of Creation. Again, I’ll quote from the story… and here is one of Machen’s most profound passages, one that reaches toward a theo-anthropology…

“It was almost dark when I got to the station, and here were the few feeble oil lamps lit, glimmering in that lonely land, where the way is long from farm to farm. The train came on its way, and I got into it; and just as we moved from the station I noticed a group under one of those dim lamps. A woman and her child had got out, and they were being welcomed by a man who had been waiting for them. I had not noticed his face as I stood on the platform, but now I saw it as he pointed down the hill towards Llantrisant, and I think I was almost frightened.

He was a young man, a farmer’s son, I would say, dressed in rough brown clothes. But on his face, as I saw it in the lamplight, there was the brightening. It was an illuminated face, glowing with an ineffable joy, and I thought it rather gave light to the platform lamp than received light from it. The woman and her child, I inferred, were strangers to the place, and had come to pay a visit to the young man’s family. They had looked about them in bewilderment, half alarmed, before they saw him; and then his face was radiant in their sight, and it was easy to see that all their troubles were ended and over. A wayside station and a darkening country, and it was as if they were welcomed by shining, immortal gladness—even into paradise.”

I think I was almost frightened. When I read this passage of the farmer I can’t help thinking of Christ… here, is yet another lovely hieroglyph, an icon… that is, the image of God in man.

So, the force that seemingly dominates the frightful landscape in The White People cannot exist on its own, for it is a parasite. There cannot be The God Great Pan without The Great Return. To choose one at the expense of the other is to handicap oneself, to fundamentally misunderstand the lifelong arc of Arthur Machen’s literature. As The Great Return illustrates, Paradise will to reassert itself. The once haunted land is doxified. The Great God Pan is dead.

In Machen’s work, it is the Holy Graal, that Hieroglyph of hieroglyphs, which returns, reveals and reclaims. When we encounter this symbol in his stories, we instantly recognize the meaning behind the symbol. It is the Light of Christ, the Theandropos overcoming darkness.

I’d like to take the time to briefly discuss a few more stories which play with these themes. In The Holy Things, Machen tells of a misanthrope who is unworthily granted the vision of a heavenly liturgy celebrated in a busy London street. A flower seller’s cry transmutes into an intoned chant as a cyclist’s bell brings solemnity. Among the pedestrians, “shapes” move and stop and move again. Quote: “But then a rich voice began alone, rising and falling in monotonous but awful modulations, singing a longing triumphant song, bidding the faithful lift up their hearts, be joined in heart with the Angels and Archangels, with the Thrones and Dominations.” The man hears Holy, Holy, Holy and no longer sees the flower seller pushing past him. This theme of periochoresis, the interpenetration of the seen and unseen, the material and immaterial, is a favorite of Machen’s and will resurface in later works such as in his final novel, The Green Round and in the excellent short story, N.

Recall the transfiguration of man as we saw with the farmer on that railway platform, because there is an experiential precedent for it in the life of our author. In the introduction to House of Souls, Machen reports:

“I got into the tram down Hackney way. There were father, mother and baby; and I should think that they came from a small shop, probably from a small draper’s shop. The parents were young people of twenty-five to thirty-five. He wore a black shiny frock coat, a high hat, little side whiskers and dark moustache and a look of amiable vacuity. His wife was in black satin, with a wide spreading hat, not ill-looking, simply unmeaning. And the very small baby sat upon her knee. I said to myself, these two have partaken together of the great mystery, of the great sacrament of nature, of the source of all that is magical in the wide world. But have they discerned the mysteries? Do they know that they have been in that place which is called Syon and Jerusalem?—I am quoting from an old book and a strange book.”

In the work of Arthur Machen, everything and everyone is a wonder waiting to be revealed. This incident would not only influence the composition of The Great Return but would become the basis for another novella: Fragment of a Life. Here, I’m going to go against the small corpus of literature known as Machen criticism and suggest that this story is Machen’s masterwork. On the outer level, it appears to be a meandering tale of a young married couple’s daily life in the suburbs. As I was reading it for the first time, I struggled with the banality: what is this about? Slowly, that outer level fell way and through various experiences, the couple comes to understand they are of Syon and Jersualem. A mystical hymn to the hieroglyph, to the icon of matrimony, it is perhaps his most perfectly executed vision, but rarely read and unsung.

The married couple, be it the pair from the story or the pair from Machen’s personal observation… it doesn’t matter which. The landscape in The Great Return or the one of Machen’s youth as recounted in his memoirs… either one you choose… man and creation show the glow of deepest truth. They are not transformed into something they were not, but transfigured and rightly revealed to be what they had been all along.

All of it is true.

This is the ecstatic alchemy of Arthur Machen, his mythopoeic vision: a perichoretic landscape built by hieroglyph upon hieroglyph, a world of symbols beneath clouds of images which seek to speak not to the intellect only, but to the nous, or the heart of the reader. He spent a lifetime and much ink illustrating, preaching, often to deaf ears, that all of the cosmos is a wonderful mystery. As he wrote: “I chose the mysteries first and I chose the mysteries last.” Indeed… even in the hundreds of newspaper articles he penned, covering every humdrum subject you may imagine, he always labored to perform the act of periochoresis to imbue in the common column space of an evening paper with this deep love of Mystery. Here is how he concludes an article on the 1915 Christmas shopping season in which he expresses a personal wish:

“I want something a little difficult, for there is no fun without difficulty; something mysterious like the jigsaw puzzle – or the Universe.”

Before I conclude, I should make a short mention of Machen’s standing in the greater world of British literature. His spirited and mythopoeic voice was admired by poets including Laureates John Betjeman and John Masefield, as well as, the greatest poet of the 20th century, T. S. Eliot. Chesterton considered Machen a prose-poet.

Before I conclude, I should make a short mention of Machen’s standing in the greater world of British literature. His spirited and mythopoeic voice was admired by poets including Laureates John Betjeman and John Masefield, as well as, the greatest poet of the 20th century, T. S. Eliot. Chesterton considered Machen a prose-poet.

Tolkien scholar Douglas A. Anderson thought enough of Machen’s position in Christian fantasy to include him in the 2002 anthology Tales Before Tolkien. C. S. Lewis wrote, somewhat facetiously, of the Angel of Mons to his brother Warnie. More interestingly, his library includes a copy of Machen’s The Secret Glory. Lewis scholars have offered a couple explanations for the book’s strange appearance on the shelf including its critique of the British education system or that the book actually belonged to Joy, Lewis’s wife. However, I’d offer a third, perhaps simple suggestion: at its heart, Machen’s most inebriated and intoxicating novel is a Grail epic.

Scholar Glen Cavaliero is absolutely certain of Machen’s impact on the third Inkling. In his study entitled Charles Williams, the Poet of Theology, he explains that the work of Machen, Evelyn Underhill and G. K. Chesterton were influential on the spiritual suspense novels by Williams. By studying Williams’s notebooks, Grevel Lindop discovered that “Machen’s The Great God Pan is noted alongside the idea that Pan might be Merlin’s father.” On Sunday, we will learn more about Machen and Charles Williams. Likewise, on that afternoon, we’ll see that Dorothy L. Sayers held a knowledge and esteem for Machen’s work. This will be explored through unpublished letters.

In the end, Arthur Machen, despite his obscurity, remains a curious and idiosyncratic flame flickering brightly in the dark night of our culture. Like the best of writers and artists, he dreamt in fire illuminating a path toward that which is most desired by mankind, an escape from dullness, from meaninglessness into delight. I hope what he has written… what he has shown.. can be received by ours and future generations.

In the end, Arthur Machen, despite his obscurity, remains a curious and idiosyncratic flame flickering brightly in the dark night of our culture. Like the best of writers and artists, he dreamt in fire illuminating a path toward that which is most desired by mankind, an escape from dullness, from meaninglessness into delight. I hope what he has written… what he has shown.. can be received by ours and future generations.

Personally, I have learned much from Arthur Machen. His uncompromising sacramental vision of the greatest and the humblest of things has changed what I read and how I read; what I write and how I write; and finally, what I publish from others. The world is a place of dangers and horrors, but all that darkness added together cannot outweigh the wonder and the glory of it. Here is the ultimate purpose to Machen’s art: to doggedly hunt down that most awful and dreadful reality – ecstasy, which lifts man from earth to the aureoles of heaven.

I close with a final word from our apostle of wonder: “Man is created to be inebriated; to be nobly wild, not mad.”

Well done! I clearly missed a lot!

LikeLike